There is nothing like an existential crisis to force a re-evaluation of priorities and policies. As Churchill said, never let a crisis go to waste, a scenario that European leaders have grasped by assembling a coalition of the willing. They must fill the void left by the Trump administration, which now has other priorities. Europe has finally realised that it must look after itself and, in so doing, confront issues its leaders have ignored for decades. Hint: it is very expensive.

As the former president of the European Commission, Jean Claude Junker said:

We all know what to do; we just don't know how to get elected once we've done it.

This time appears to be different. Yet, being willing to change is one thing; being able to affect it is something else. Execution entails leadership and cohesion around strategic priorities, something the EU isn't renowned for, as Henry Kissinger once wished he'd said,

When I want to talk to Europe, I don't know who to call.

Nowhere in recent weeks has the cold wind of change been felt more than in Germany. At a time when it theoretically doesn't have a government, Europe's industrial workhorse, financial underwriter and liberal conscience, over a matter of days, made plans to rip up its constitutional defence spending limit and jettisoned its sacred fiscal debt brake.

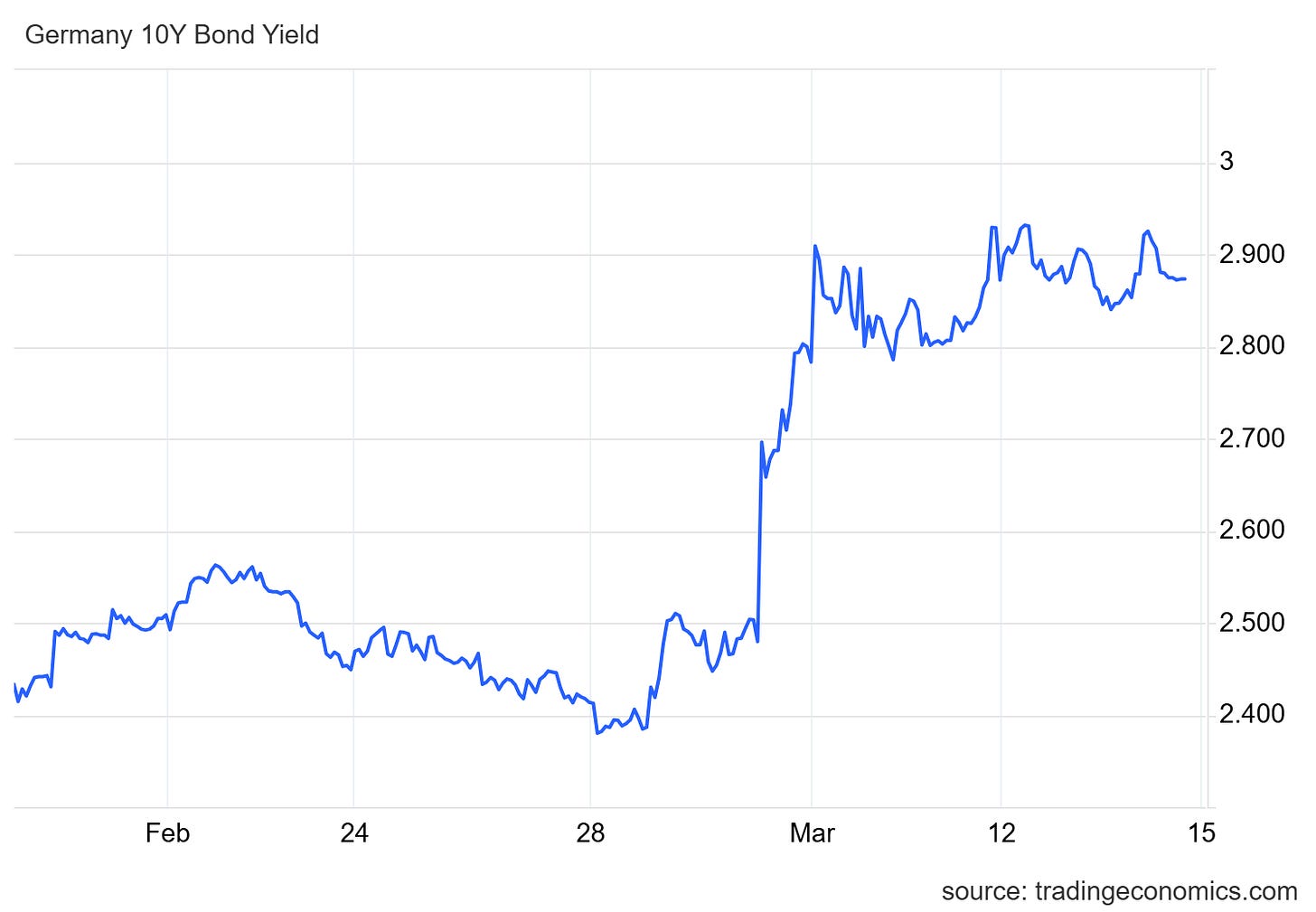

In response, its bond yields (borrowing costs) rose to levels not seen in thirty years, and its sluggish equity market sprang to life. Year to date, while the NASDAQ is down 10%, the DAX is up 15%, an outperformance that was not on many investors' bingo cards for Q1 2025. A potential trillion Euro stimulus package from Europe's most financially cautious nation acted as high-voltage shock therapy to a region recently ossified in economic stagnation. The world's biggest value play got an era-defining catalyst as it attempts to turn its lumbering economy on a dime.

For those who think capital flight from the US to Germany is a multiyear trend but are concerned that the sharp rally in German equities means you have missed the boat, think again. The market cap of the DAX 40 largest listed companies in Germany is less than the value of Amazon, suggesting that there is much further for this boat to sail.

In the UK, Keir Starmer has also sprung to life, enjoying his best few weeks in office since last summer's election, flush from his successful trip to Washington and keen to form a functional bridge to the rest of Europe. Offered the chance of a US trade deal lifeline for his country and his political future, Keir senses his Falklands moment. As the nation's biggest populist parliamentary party beats itself up in a phone box, the UK PM is quietly stealing its clothes, slashing NHS bureaucracy, trimming welfare spending and leading the external challenge confronting the coalition of the willing bravely entering its “operational phase.”

This new version of Starmer has shown he is prepared to create internal division within his party and cabinet to widen his popular appeal. He and his advisers are racing Farage to the centre ground of British politics before the next election. In so doing, he is not quite causing a Trumpian level of chaos but a quieter British take on the same theme; perhaps it is too much to expect him to wield a chainsaw at the party conference, but it appears that something might have been put in his tea at the Oval Office.

Keir 2.0 has claimed that his defence spending boost will benefit his top priority, economic growth. Like the green transition, he said it will create thousands of well-paid jobs for good, decent working people. This simplistic assertion is fraught with problems. First, the West has only recently left (before 2022) the post-Cold War peace dividend era, coinciding (causally) with falling bond yields and steady non-inflationary growth. Can we believe a sharp reversal of this trend is also beneficial?

According to No 10,

the investment in defence … will … create a secure and stable environment in which businesses can thrive, supporting the government’s number one mission to deliver economic growth.

Second, see the German bond yield example above for a real-time example of what capital markets think is the effect of higher defence spending on an economy.

Stephen King of HSBC tackled this issue very well in his Times article, Will higher defence spending juice the economy? Think again. King’s point is similar to the French economist Frederic Bastiat’s parable of the broken window, an insight that rejected Keynesian orthodoxy years before the over-promoted mathematician was born.

AI agent Grok takes over,

Bastiat’s story goes like this: A shopkeeper’s window is broken by a careless kid. The shopkeeper has to pay a glazier to fix it, say, six francs. Some onlookers argue this is good for the economy—after all, the glazier gets work, spends the money elsewhere, and stimulates economic activity. This is "what is seen." But Bastiat points out "what is not seen": the shopkeeper, now six francs poorer, can’t spend that money on something else—like a new pair of shoes from the cobbler. The net result? No real economic gain, just a redirection of resources. The broken window doesn’t create wealth; it destroys it (the window’s value) and forces repair spending that cancels out other potential uses.

Meanwhile, back in Washington, Trump’s team also faces important dilemmas. Everywhere in its interactions with the rest of the world, whether sorting out the hot wars in the Middle East or Eastern Europe and trade wars, real or imagined, it demands to be taken literally and seriously and also with a suitable respect for being, in the historical analysis of 1066 & All That, Top Nation.

Trump feels the world gives the US a bad wrap; he wants to do something about it. He wants to MAGA and only has four years to do it. However, this time, he is better equipped to enact policies often thwarted in his first term by political opponents and an uncooperative administrative state. Now, with a team of committed and capable loyalists such as Lutnick (trade), Bessant (treasury), Vance (attack dog) and Wright (energy), the adage that Trump should be taken seriously but not literally is wearing a bit thin. The problem lies in the inconsistencies contained in his various MAGA objectives, inconsistencies which are beginning to show through.

Just as European allies realised that the new administration should be taken seriously and literally about taking care of their own defence, Trump’s former allies on Wall Street now realise they, too, are on their own; there is no Trump Put. Secretary Bessent has taught his new boss about taking debt seriously, something Trump made a career out of ignoring. As Bessent explained, the new administration’s interests are more closely aligned with Main Street, where they share the same desire to sensibly refinance its debt, a small matter of c $9 trillion of Treasuries this year. An economic slowdown (maybe a recession) is a price the Treasury is prepared to pay for this to happen.

So, unsurprisingly, US equity investors have responded and dented the concept of American exceptionalism. As HyperNormalTimes said on January 20th, in What Price American Exceptionalism?

Over the next four years, non-USA markets will likely become better homes for capital. With the US equity market priced for success (see chart below) and the rest of the world priced to fail, there is an opportunity to skate towards where the puck is going next. However, unlike Gretsky, we cannot know the timing of such moves.

The always excellent Le Shrub illustrated it using the Uno reverse card.

If you listen to one macro analysis of world markets this week, I suggest Julian Brigden on Monetary Matters, describing markets undergoing a rotation trade of biblical proportions.

On Spotify

or YouTube

Barry Norris at Argonaut is always good for a pithy update on how long-short investors think about it. (I particularly liked his explanation of the difference between AfD and Adolf Hitler’s political philosophy, a point often overlooked by most media outlets).