What Price American Exceptionalism?

How to play the changing world order on the eve of Trump 2.0

America is exceptional, but the basis for its exceptionalism has changed over time. The dollar's global significance, fiscal stimulus, AI enthusiasm, and optimistic expectations for Trump 2.0 have created a US equity bubble. The consequences of the bubble ending are more knowable than its timing. Fund managers at Argonaut and Ruffer offer differing analyses and coping strategies. Both can be successful.

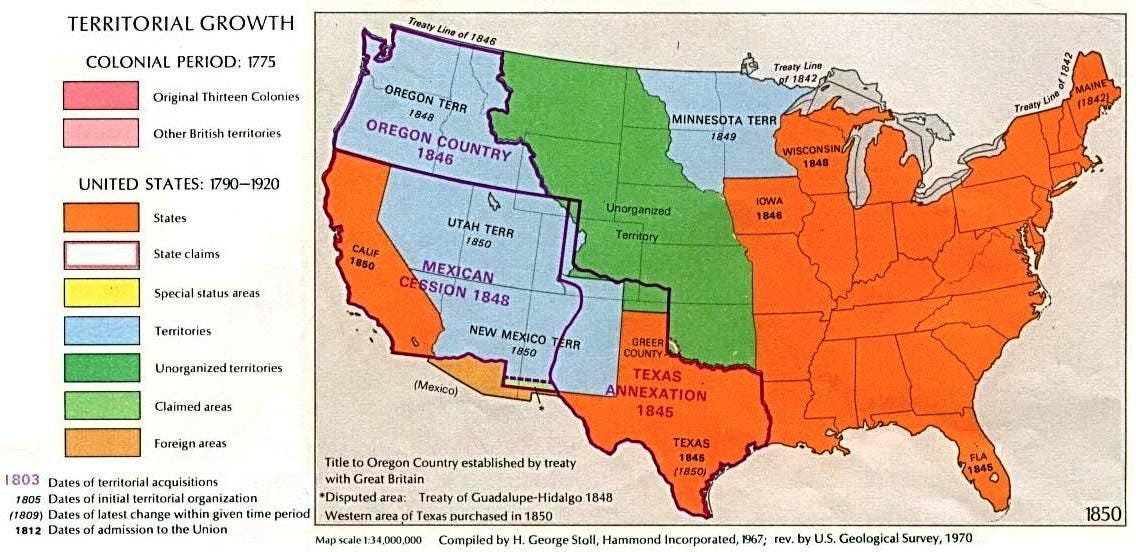

In 1776, fifty-six delegates from just thirteen colonies signed the US Declaration of Independence. It took another seventy-five years of war, land purchases, annexation, and treaties for the broad outline of modern-day America to take shape. It wasn't until the 1950s that Alaska and Hawaii became the 49th and 50th states. If you pause to consider that about halfway through this timeline, the country had a devastating civil war capable of destroying the economic lifeblood of less resilient nations, modern America can truly be considered exceptional.

The pinnacle of American exceptionalism probably occurred between 1945 and 1973, beginning with the victory in World War II and ending after the withdrawal from Vietnam. The Vietnam War's inflationary and fiscal impact forced the US to abandon the last vestige of dollar-gold convertibility, which, combined with successive Middle East oil crises and recessions, resulted in the financialisation of the US economy and the dollarisation of the world.

In the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, what was good for GM was considered good for the US economy; post-1980, the criteria changed to what was good for Goldman Sachs. Over the following forty years, the US surrendered its manufacturing base first to Japan and then to China, as its consumers enjoyed plentiful imported low-cost goods.

All this occurred with the tacit understanding that the surpluses earned abroad would be recycled into dollar assets, mainly Treasury Bonds. Globalisation had neutered America's industrial might but secured its place as the unchallenged military hegemon, defending the dollar and enforcing its exorbitant privilege to print them. As Treasury Secretary John Connally told European politicians in 1971, the dollar was "our currency, but your problem."

As Lyn Alden put it,

Since the 1970s, the United States has encouraged countries to hold dollars as their primary reserves. Even without this encouragement, the post-Bretton Woods network effects of the eurodollar system were already strong compared to other currencies. Most cross-border trade is priced in dollars, most cross-border lending is denominated in dollars, and accumulated trade surpluses are stored primarily in dollars. The dollar is the most salable currency and thus serves as the world's primary ledger.

American exceptionalism shaped the 20th-century industrial age and led the financialisation of the developed world. It has since manifested its supremacy in the digital age. The mastery of AI and its potential as the defining general-purpose technology of the 21st century has been particularly significant.

Today, what is good for the US economy is good for the gargantuan Mag Seven big tech companies. The incoming Trump administration's tech-bro creds outweigh its Wall Street connections, and its quest to make America great again results from an unlikely coalition of Rust Belt Deplorables and Silicon Valley Accelerationists.

As the Ruffer team summarised it in its latest review:

The US economic powerhouse has many unique institutional and geographical advantages. Beginning after the GFC, the bull market grew on American technology leadership, energy independence and superior demographics. Latterly, it was given a shot in the arm by huge relative fiscal stimulus in response to the pandemic and during the Biden administration.

Barry Norris at Argonaut notes:

Since [the GFC], whilst GDP per capita in the US has risen from $48k to $78k, living standards have remained stagnant for 15 years in Western Europe.

And that,

America has 242 companies under 50 years old with a current market value above $10bn, grown from "scratch" without major acquisitions. By the same criteria, Europe (including the UK) has only 15. America celebrates its entrepreneurs, seeing their success as a triumph of free will.

Norris refers to Writson's Law, which states that capital (financial and human) flows to where it is best cared for. Unsurprisingly, Norris is still invested in the US.

He says,

Whereas Trump promises further business deregulation, smaller government, lower taxes and cheap and reliable energy, in an act of economic euthanasia, policies in the UK and Europe continue to advocate the exact opposite, with its political class doubling down on failure.

Norris believes American exceptionalism has more to offer investors and that investors, like Ayn Rand's Atlas, should shrug off Europe and continue to allocate capital to the US.

As he put it,

The re-election of Donald Trump as US President has reinforced American stock market exceptionalism and will further highlight the abject failure of the European economic model.

However, the Ruffer team points out that:

Minsky taught us that the danger is greatest when perceived risks are most benign, and only 6% of the fund managers surveyed believe in a US hard landing in 2025.

Furthermore, most investors are so invested in the American exceptionalism thesis that its stock market value now accounts for over 70% of the MSCI global developed markets index.

As Ruffer put it,

A country that makes up 4% of the global population, 26% of global GDP and a third of global profits account for a staggering 70% of global equity indexes. We have not seen such an imbalance for many decades. The only comparison was in the late 1980s Japan, which contributed less than 20% of the global GDP but made up 45% of the MSCI World.

Indeed,

The seven biggest US companies in the MSCI World Index have a larger weighting (20%) than those of Japan, India, Switzerland, France, China, the UK, and France combined.

Trump's second term promises high ambition but even higher uncertainty, implying higher return variability. Nowhere is uncertainty more impactful than the future direction of the dollar: a strong dollar, usually a requirement for reserve currency status, or a weak dollar that would help rebuild America's export potential.

Larry Summers epitomised dollar exceptionalism by saying that,

Europe is a museum, Japan is a nursing home, and China is a jail; we don't need to worry about those currencies being a major threat to us.

For Norris, the dollar and US capital markets remain unchallenged by Europe.

In their words and deeds, the [UK's] new Labour government has already created the impression that the UK is now a non-profit organisation.

Investors are constantly told—mostly by UK fund managers—that the UK stock market is "cheap." Under the current political regime, it is likely to remain so. But after 5 years of hard Labour, we might just decide that the economic model that post-Brexit Britain should copy is Trump's America rather than failing Europe. Until then, and when considering the additional burdens placed on capital, investors – like Rand's Atlas – should shrug and invest in Trump's America instead.

Norris successfully bought exposure to Argentinian equities last year, as the Milei government made global capital more welcome, and its stock and bond markets soared. He identified what Wayne Gretzky advocated by moving to where the puck is going, not where it is.

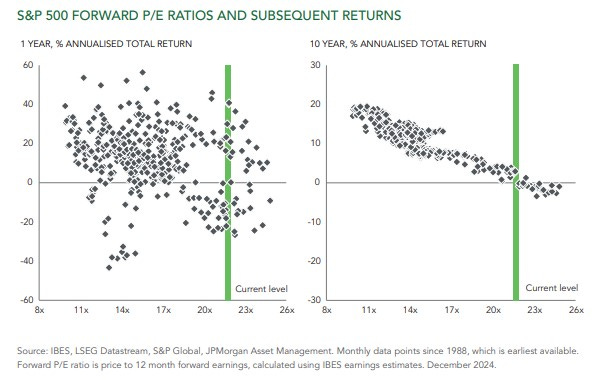

As Trump presses renewed confidence in American exceptionalism, his administration has already caused significant changes in Canada, Europe, and the Middle East. He may also affect change in China. As a result, over the next four years, non-USA markets will likely become better homes for capital. With the US equity market priced for success (see chart below) and the rest of the world priced to fail, there is an opportunity to skate towards where the puck is going next. However, unlike Gretsky, we cannot know the timing of such moves.

The Ruffer Investment Company and Argonaut's Absolute Return Fund offer different methods of downside protection. Argonaut has returned 50% over the last three years, while the Ruffer fund is down 10%. I own both and am confident that the Ruffer Fund will eventually outperform. However, I don't know when that time will be, so I will continue to hold both.