Capital moves to where it is best cared for. For the last fifteen years, global investors have been habituated to the idea that this was and always will be the US with its constitutionally defined freedoms, protection of property rights, and vast dollar capital markets dominated by best-in-class technology companies. However, although King Dollar clings to its exorbitantly privileged world reserve asset status, the new Trump administration is pushing back against its attendant responsibilities of being the world's policeman and protector.

Meanwhile, America's colossal capital base has started to leak. We don't know whether this is a financial market adjustment (a temporary mean reversion) or the start of a global economic restructuring akin to the collapse of the Berlin Wall. Either way, there is growing concern that the bill is coming due for 35 years of hyper-globalisation and the significant unintended consequences its "end of history" hubris unleashed. Increasingly, those who previously said we didn't need to take Donald Trump literally with his intention to collect on this bill are starting to re-assess their assumption.

For those who weren't present or don't remember, it is worth reflecting on how the West has changed since the millennium. In those heady 1990s days of peak global liberalism, when the US State Department and NATO felt confident that they could bomb other countries into democracy and when Vladimir Putin was an unremarkable former Soviet KGB agent, Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, and the EU campaigned for the admittance of China to the World Trade Organisation.

The argument was that if we freely traded with China, they would come to adopt the superior norms of liberal democracy. As the Germans put it, wandel durch handel (change through trade). If we trade with them, they will become more like us. However, in the intervening quarter of a century, the West has moved towards authoritarianism more than the nations it was trying to help have moved towards democracy.

A cursory glance at the Q1 performance of financial markets year to date indicates the extent to which the world's capital might have begun an era-defining rotation. The dollar's trade-weighted value has fallen 5%, unusually, when equity market volatility, as measured by the VIX, rose. Significantly, the safe haven asset of choice remained gold, which continued its relentless rise, up nearly 20% in the period and up by more than 50% in $ terms over the last 3 years.

However, equity market divergence illustrates the end of the American Exceptionalism thesis most vividly. Trader Le Shrub and global investor Sean Peche at Ranmore observed what Peche describes as the unintended MIGA Movement (Make International Great Again). They point to the heightened requirement for geographical diversification as the world unwinds from its excessive reliance on (expensive) US assets. Just as the White House seems more interested in bond yields than the health of the equity market and where cabinet members with economic briefs refer favourably to an upcoming period of economic detoxification.

It is worth remembering exactly how invested equity markets had become in the American Exceptionalism Thesis after Trump's November election victory. The following are Tweets from famous investors and commentators post November 5th, unattributed to avoid embarrassment:

Trump's win is a steroid shot for stocks—small caps are up 5%, banks are roaring, and Tesla is +15%. This is the most bullish setup I've seen in years!

Wall Street's throwing a party—Dow's biggest day EVER, S&P up 2.5%, banks like Goldman up 10%. Trump's win is a corporate jackpot!

TRUMP WINS: Dow +1500, Bitcoin $75k, yields spiking—markets are pricing in the golden age of deregulation and tax cuts. Buckle up; this is just the start.

TRUMP TRADE in full swing—Dow futures up 1200 points, Nasdaq futures surging, banks and energy stocks ready to rip. Markets are screaming: America's back, baby!

This is the most pro-growth, pro-business, pro-American administration I've perhaps seen in my adult lifetime.

However, five days after his inauguration, a Chinese tech company that few had ever heard of announced its new AI agent, DeepSeek-R1. Critically, the technical details claimed the company had achieved its milestone in a far less compute-intensive manner than typically adopted by the Mag Seven present at Trump's swearing-in. Since then, Nvidia has lost 29% of its value, while Alibaba has gained 62%. The wider NASDAQ 100 is down 12%, and the Hang Seng is up 18%.

Just three weeks after DeepSeek set the cat among the Mag Seven pigeons, VP JD Vance arrived to address Europe's leaders at the Munich Security Conference, confident he would remind his audience of the consistent rhetoric of all recent past presidents for the need for European self-reliance in defence. Oh yes, and if you could let those nice people in the AfD into your cosy coalition politics, that would be great, too, and please look the other way while we agree on a deal with Ukraine and Russia, which you will pay to enforce.

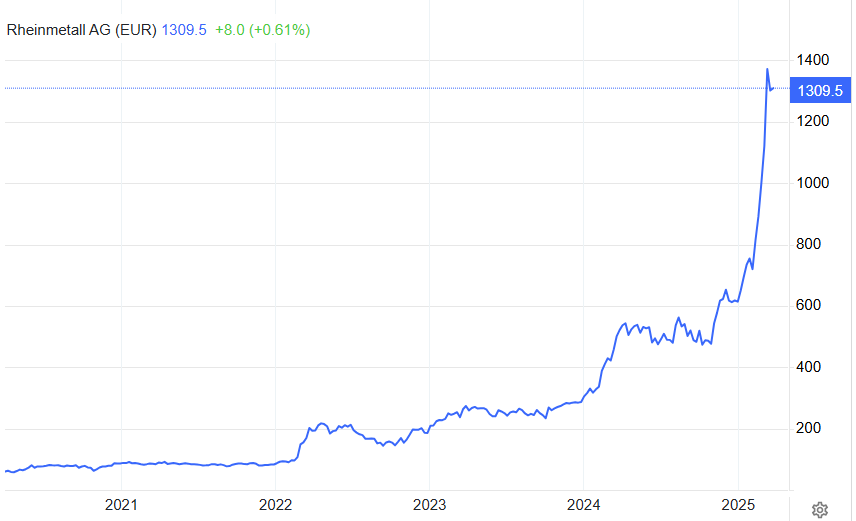

As Vance spoke, German defence company Rheinmetall, whose shares had risen nearly tenfold in price since the invasion of Ukraine three years earlier, were trading at approximately Eur 750; a month later, they were up another 75% above Eur 1300.

More widely, Germany united behind its common external threat and released its fabled Federal government debt brake to blast up to a Eur 1 trillion stimulus into its sclerotic economy. The Euro rose 5% against the dollar, and the DAX40 roared to a 12.5% Q1 gain. For dollar-based investors, the VP's speech caused a loss of over 20% versus the S&P 500 in a matter of weeks.

Within a month of his inauguration, the man the markets believed would open the door for the USA's golden age had seen equity markets in China and Germany power past its global champions. But what of the UK? Amidst the start of what might become The Great Rotation, what are its prospects?

Over the period, the FTSE 100 recorded a nearly 5% gain, but the FTSE 250 and AIM indices recorded small losses. Before their recent re-ratings, the UK shares China and Germany's previous out-of-favour value characteristics. Still, without the positive catalysts each of those markets has seen, the UK funds flow data indicates that it remains friendless. Despite the Bank of America asset manager survey suggesting the most significant one-month allocation away from US equities in memory, precious little seems earmarked for the UK.

Any rational analysis of the UK's spring statement from Chancellor Rachel Reeves helps explain why this might be. While Germany and China roll out the carpet for global capital, the UK sometimes appears to be putting up the shutters. Like her better-qualified counterpart at the US Treasury, Rachel's primary focus last week was to pacify bondholders rather than soothe the nerves of equity investors or even pander to the desires of her own Westminster party colleagues.

The spring statement is a performative act of fiscal discipline and rectitude that puts lipstick on a pig while kicking the crucial decisions down the road to the Autumn budget. Meanwhile, her wafer-thin margin for error in her fiscal rules could be blown away by one sweep of Trump's tariff pen, a spike in rates, or a run on the pound.

However, Reeves took the opportunity to move the blame for her dilemma from the inherited Tory mess to the prospective perils of the uncertain Trump world trade environment. This is even though the main impact of her increased employment taxes and her government's new worker rights legislation has yet to be felt by long-suffering companies and taxpayers.

So, should investors despair and give up hope for the UK? The Great Rotation still offers UK investors hope. The world's over-allocation to US assets was driven to higher highs by dumb, passive flows, perpetuating the known nature of US exceptionalism. So far in 2025, all we have seen is a suspicion, as yet unverified, that the world economic order is undergoing a structural change. The Great Rotation will be driven by individual agents creating unforeseen emergent outcomes by taking what investors call active share. As Sir John Templeton said,

You don't beat the market by replicating the market.

The UK represents just 3.6% of the MSCI World Index, a rounding error for most global portfolios. We can all come up with a list of six things that the UK could do better to promote economic growth and generate activity in its capital markets. China and Germany have shown how dramatic asset price action can be when unexpected catalysts occur. Indeed, we can see these impacts in individual UK stocks when results are not as bad or are even better than expected.

Cheer up and remember, it is darkest before dawn and just before you die.