When you suppress volatility and randomness in a system, you create fragility. Centralised interventions remove the small fires that keep a forest healthy, leading to a massive conflagration later. Antifragile, Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

Understanding the nature of uncertainty and risk helps us consider how to mitigate their impact or even benefit from them. If you want to read about Argentex and Alpha Group, then scroll down to the share button.

Last week, Iberia went dark. Its power grids collapsed due to a lack of inertia, a form of redundancy inherent in traditional power generation methods. Like financial markets, power generation and transmission are highly regulated activities and, in recent years, have been regulated with the overriding goal of reducing carbon emissions. What caused the unexpected failure of this highly complex system was oversight negligence. A lack of provision for the unintended consequences this policy objective had created. Financial regulators who overly focus on reducing volatility in our financial markets should pay attention.

Fewer things have been more certain in stock markets recently than the outlook for most companies is less certain. As the person blamed for this greater uncertainty celebrated his 100th day in office, markets displayed more composure than in recent weeks. Short-term system-wide de-leveraging had helped calm nerves, and some risk-seeking behaviours returned. Bitcoin outperformed gold by 25% in two weeks. A sure sign that the speculators were returning to the casino.

However, financial market risks are not casino-like probability events. Tarrified investors can sense that the unintended consequences of the Trump tirade on the world trading system have permanently exacerbated financial market dislocations, creating second-order consequences of unknowable impact. Indeed, such risks have already become apparent in some unexpected places that, perhaps, should have been expected.

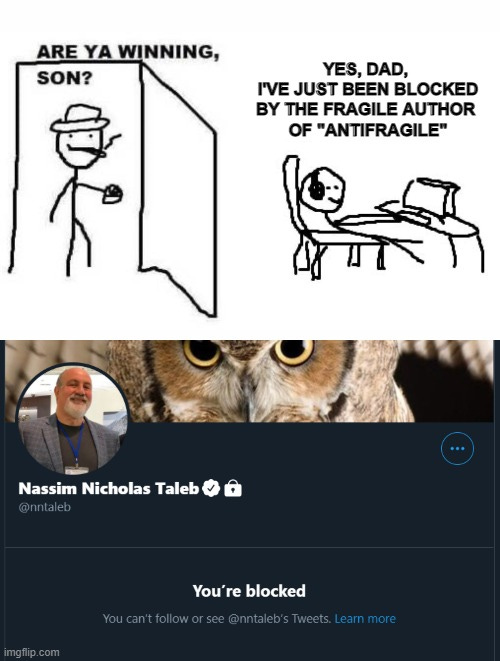

As unprepared markets were absorbing Liberation Day's chaos early last month, I got to talk with David Dredge at Convex Strategies. It was a welcome relief to find someone whose outlook on markets and life seemed destined almost to enjoy such moments of pain felt by others. More than anyone, Dredge colours in the real-world implications of the theoretical framework explained by his former colleague, the author and NYU Professor Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Bear markets and drawdowns are the time for the doomsday preppers to remind us that we should have been more careful in our investment strategy. As if we needed the reminder!

But, as convexity bulls see it, through the eyes of Taleb's writings, we are all too often fooled by randomness, and when a black swan arrives, our [anti]fragile world is shattered by an absence of skin in the game. When the world's markets have enjoyed the most extended period of stable correlation and reduced volatility in recorded financial history, it is easy to dismiss such alarmists as modern-day wolf criers. However, the world has changed, and the forcing function provided by the new US administration is a powerful example of how the risks inherent in our daily exposure to financial markets have also changed.

Critically, for Dredge and Taleb, risk is not volatility. Dredge sees danger in a world that not only equates these two concepts but also, counterintuitively (and absurdly), infers that upside and downside volatility are equal. For him, risk isn't what you think will happen; it's what hurts when it happens. Risk is about our vulnerability, and it impacts people differently.

Dredge rejects the conventional Sharpe World view of financial theory that certain assets are inherently risky or riskless. As he says, we live under regulation by a Sharpe World where,

By definition, bonds are risk-reducing to a portfolio because they negatively correlate with equities. This correlation has only existed since Alan Greenspan innovated the Central Bank reaction function in the 1990s.

But as he sees it, bonds have been used as a means of financial repression for decades, as Sharpe World regulators, responsible for creating accounting warehouses where risk-free assets can be accounted for favourably for short-term compensation purposes and yet ignore the systemic risk inherent in accumulating leverage. As he said, Silicon Valley Bank went bust by leveraging what it accounted for as riskless. In his parlance, it displayed the behaviour of Rational Accounting Man, so beloved of regulators but with devastatingly systemic consequences.

No one, he says, represents the Sharpe World more than that "very nice lady," Janet Yellen. Dredge compares his former Berkeley economics professor to his mother. He said both are elderly, round, well-read, and well-meaning. But neither knows anything about money, which for his mother, an attorney, is not a problem. However, for Yellen, the only person to have been chair of the President's Council of Economic Advisers, Fed Chair and Secretary to the Treasury, it is a problem.

For Yellen, economic history is a series of random exogenous shocks that the control levers of financial regulation must correct. If that correction creates a new problem, it too will be corrected until the system (i.e. us) learns to behave as the models expect, and we become Rational Accounting Men.

In the UK, you might substitute Janet Yellen with Gordon Brown. Hailed as the greatest of the UK's postwar Chancellors, Brown granted independence to the Bank of England and presided over a prolonged period of strong economic growth until he didn't. In a moment of peak Sharpe World hubris, in his 2006 Budget speech, Brown said,

Britain has now enjoyed the longest period of sustained growth since records began… We have put an end to the cycles of boom and bust.

So confident was Gordon Brown that in his Chancellery, pulling fiscal levers and the independent Bank of England pulling monetary levers, he believed he could manage the UK to a permanently elevated plateau of wealth and prosperity. Confident he could control the economy and manage the risks the financial system faced, he decided the UK's reserves had no place for what his mentor, Lord Keynes, called the barbarous relic of monetary history: gold.

Shortly after assuming power, Brown sold nearly 60% of the UK's gold reserves, over 400 tonnes, at an average price of $275 per oz. raising a total of $3.5bn. It would be worth $42bn (twelve times the amount) today. What Gordon Brown forgot when assessing the make-up of the UK's reserve asset portfolio is the one dependable free lunch available to all investors: diversification.

Global value investor Sean Peche's fundamental tenet is that the future is unforecastable, and diversification is the best method to deal with this reality. Peche has evolved a practical way of protecting his investors via a 50-stock portfolio, each with a 2% allocation. But rather than just buying the fifty cheapest stocks at each rebalancing, he applies other risk-reducing overlays, developed as proven risk mitigants, improving favourable risk asymmetry.

Implicitly agreeing with Dredge about confusing volatility with risk, Peche seeks risk profiles that skew toward the more attractive upside right tail by avoiding overly indebted balance sheets and cheap typewriter companies, known as value traps. Another way to mitigate risk is to be what he calls geographically agnostic and seek out relative value in macro-impacted areas of the world. Recently, he moved his UK weight up to 11% and has been underweight in the US for some time.

Meanwhile, Lawrence Lam, fund manager of the Lumenary Global Founders' Fund, seeks risk asymmetry by investing in the founder effect. For Lam, after a low level of portfolio diversification, his primary source of risk mitigation is investing in people with greater concentration risk than him. But importantly, he backs founders who have already demonstrated domain expertise and superior long-term decision-making capabilities, resulting in financial health metrics closely aligned with customer and shareholder well-being.

Lawrence owns UK FX and payments provider Wise in his global portfolio, which is a classic exemplar of his founder effect. His screening also flagged Alpha Group International (formerly Alpha FX) as having similar attributes. This latter point confirmed for me that his screening had validity. Having known Alpha and its founder, Morgan Tilbrook, since its IPO in 2017, I interviewed him three years ago, and his authenticity spoke volumes about the determination for his business to succeed, driven by a fear of failure and imposter syndrome. Since its IPO, Alpha's share price has delivered an 11-fold return based on its founder-led mentality and decentralised management style, backing incentivised high-quality people enhanced by a well-invested tech stack.

However, the financial market consequences of the COVID lockdown severely tested Tillbrook's fear of failure when, in 2021, he revealed a problem with a forward FX contract and a customer liquidity issue impacting the company. COVID had hit hard, raising the credit risk among its customer base, and historic levels of FX volatility further compounded things. We might never know how close these conditions took Alpha to the edge of solvency, as, led by Morgan and his management team, Alpha swiftly implemented a recovery plan supported by an equity raise to see it through this extraordinary period.

Fast forward to 2025, and amid similar economic uncertainty and FX volatility to 2020, it is instructive how another corporate FX provider, Argentex, fared. In its results presentation recorded via the Investor Meets Company site on April 2nd, Argentex management reiterated its previous belief that it would, if anything, benefit from the increased uncertainty and FX volatility expected due to the new Trump administration. Its management team spoke of their success in reducing headcount costs while introducing three LTIPs to incentivise them to grow the top line, which would benefit them under the heightened uncertainty. In the Q&A, they confirmed that the current management team and board, excluding PE backer Pacific Investments, owned 2% of the outstanding equity and that the one-off costs of £2.7m incurred in 2024 were primarily accounted for by replacing the previous management team and terminating an inappropriate LTIP scheme.

After the long Easter weekend, later that month, Argentex put out the following RNS:

Update on Financial Position

Suspension of trading on AIM

Argentex Group PLC (AIM: AGFX), the global specialist in currency risk management, provides the following update regarding its financial position.

Following the Company's recently published FY24 Annual Results on April 2nd 2025 and subsequent associated results investor roadshow, Argentex has been exposed to significant volatility in foreign exchange rates, particularly in relation to the rapid devaluing of the US Dollar against other major benchmark currencies which has been precipitated by the various recent announcements from President Trump regarding tariff policies and US government spending cuts.

As a result, the Company has experienced a rapid and significant impact on its near term liquidity position, driven by, inter alia, margin calls linked to its FX forward and options books. The Company has taken a number of steps to preserve cash and increase the collateral received from its counterparties. In addition, the Company is considering a number of options for the business. The Company also has the support of its principal liquidity provider and is in discussions with them regarding ways to further strengthen its liquidity position given the ongoing macro uncertainty, noting the likelihood of continued volatility in the currency markets and the associated exposure presented within the Company's FX forward and options books. In the event that the volatility in currency markets worsens materially then the Company's financial liquidity position, if not strengthened in the near term, would be significantly stretched.

In light of these developments and the current material uncertainty, the Company also announces that it has requested a suspension of trading in the Company's ordinary shares on AIM with effect from 07.30 a.m. today.

And with that, Argentex was no longer a solvent independent entity. While equity owners look likely to receive 2.5p per share for their troubles (about 6% of the pre-suspension value), they are unlikely to retain any future upside from the business under the IFX proposals, including a bridging loan on which Argentex has already requested an extension.

It is easy to be clever after the event, and I have no intention of underplaying the difficulty of dealing with the liquidity and solvency issues confronting such situations as Argentex faced. Managing risk is often not significantly mitigated by following the regulatory framework, which I am confident Argentex was.

However, a comparison of the incentive structures with Alpha is helpful. Founder Tillbrook still owns 12.5% of the equity despite giving in to his imposter syndrome last year and handing the CEO reins to former Chairman and Travelex co-founder Clive Kahn. However, the Argentex incentives appear to allow the management to participate in the upside without fully sharing the pain of the downside. They were flying the plane with parachutes.

So, how did Alpha fare in the recent bout of heightened uncertainty, the second time around? One might have thought the shares could echo past concerns and sell off in sympathy with its smaller competitor's difficulties, but if they did, I missed it.

Ahead of the May Bank Holiday on Friday, May 2nd, Alpha's larger US-listed payments competitor, Corpay, announced it was in discussions with Alpha regarding agreeing on an all-cash offer for the business. While an offer might not be agreed, this development does signify that an entity with established domain expertise believes Alpha FX to be an additional risk worth taking. Underscoring the resilience developed by Alpha five years ago, illustrating convexity at work and perhaps even some antifragility to boot. Dredge and Taleb might approve.

Meanwhile, the debate in the UK rages about whether it is subject to a systemic grid collapse of the type experienced by Spain and Portugal a week ago. There was an intriguingly timed intervention from Tony Blair, a man with better political antennae than his surly and dogmatic successor, Gordon Brown. Ahead of Labour's first electoral test of the new parliament, the architect of New Labour suggested the all-out pursuit of net zero might not be the best course of action. His intervention is unlikely to have been coincidental, but instead some much-needed coordinated air cover for Keir Starmer to pivot on this crucial growth-boosting opportunity, of course, when the time is right.

Such a tack away from net zero is Starmer's best hope in 2029, not for the sake of the UK power grid's growing operational fragility, but for the prospects of retaining power. After all, that is the principal uncertainty that concerns politicians.