Last Year

Just over a year ago, several US regional banks with balance sheets stuffed with "risk-free" US Treasuries collided with the Fed's sharp rate-hiking cycle. The fallout resulted in the managed demise of three significant regional banks: Silvergate, Silicon Valley, and Signature. Policymakers quickly eased financial conditions. The Fed opened an emergency discount window to allow banks to liquidate bond positions anonymously and at artificially inflated prices, and the Treasury allowed its account at the Fed to run down aggressively and focus its debt issuance on short-dated bills, accessing reverse repo deposits.

Treasury Control

Financial markets blinked and wobbled but recovered as bond yields fell with the cushion of increased dollar liquidity. The Fed's duty to preserve order in the US financial system took precedence over its duty to fight inflation. However, with this monetary easing that wasn't QE, the Fed ceded control of the economy to the Treasury Department, which it fully embraced. The result of this assertion of fiscal dominance boosted the economy but also made inflation less transitory.

Rates Peaked

A few months later, the Fed's mood music changed. Compared to his previous year's hawkish homage to Paul Volcker, Chair Powell began to signal that the hiking cycle had peaked at its annual retreat in Jackson Hole. Memories of Silicon Valley Bank and the unprofitable dog-walking apps it financed faded. However, behind the scenes at that gathering of the world's central bankers was a prescient warning from Berkeley economist Barry Eichengreen. This is from What Worries Central Bankers in August last year.

The clear message [...] was to expect more prolonged levels of increased government borrowing combined with increasingly fragile secondary bond markets. In short, the Treasury needs to sell more debt, and the markets have limited capacity to handle it. Eichengreen added an interesting unnamed reference to Japan in his paper: "Countries where the central bank has purchased the entirety of net new debt issuance over the last decade may have considerably less room to run; in particular, conditions may change abruptly when quantitative easing gives way to quantitative tightening" - a stark reminder that Japanese normalisation represents an under-rated but significant tail risk to global markets.

Party Time

To say that markets failed to heed Eichengreen's message would be an understatement. What do these academics know about the cut and thrust of markets? Following further upbeat Fed signals about the end of the rate hiking cycle and their future downward path, US 10-year Treasury yields collapsed in the following months by over 100 bps to 3.9%. As we know, this led to a Q4 frenzied global rush into risk assets. When Uncle Jay says rates are coming down, markets don't stop to ask questions.

Not So Fast

Following successive data releases this year showing a stronger-than-expected US economy with stickier-than-expected inflation, Mr Eichengreen's warning shot has its sights now firmly set on the world's biggest bond market. As US 10-year yields blow out again towards the level we saw last year, financial markets are again starting to wake up to what is happening in the world's third-largest economy, its currency and its inextricable links to global markets.

Let's revisit Japan's parallel universe and see how we got here.

Top Nation

By the end of the 1980s, Japan's stock market accounted for 60% of the global equity market. Japan led the world in car and semiconductor manufacturing, consumer electronics, and banking. The real estate value of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was estimated to be greater than that of California.

Debt Deflation

However, over the subsequent 30 years, Japan's GDP barely changed, and its stock market has only recently reached its 1989 highs. Furthermore, Japan is ageing at an alarming rate. Based on current trends, its population will be extinct in 300 years. Japan has suffered an almighty debt deflation problem, and in 2002, the BoJ introduced a novel monetary policy called Quantitative Easing to inflate away its problems.

YCC

The Bank of Tokyo's policy rate has averaged zero for over a decade, and free money has become an accepted part of everyday life. Despite its QE policy, Japan's inflation rate remained stubbornly low. So, in 2016, the BoJ went a step further and began a policy of controlling interest rates further along the curve, called yield curve control (YCC).

All ZIRP Together

As the BoJ bought ever-larger quantities of Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs), its national debt ballooned, culminating in an eye-popping 263% net debt-to-GDP ratio funding the BoJ's majority ownership of JGBs in issue. But no one seemed to care as the rest of the world locked down and followed Japan's path to extreme QE and near-zero interest rates.

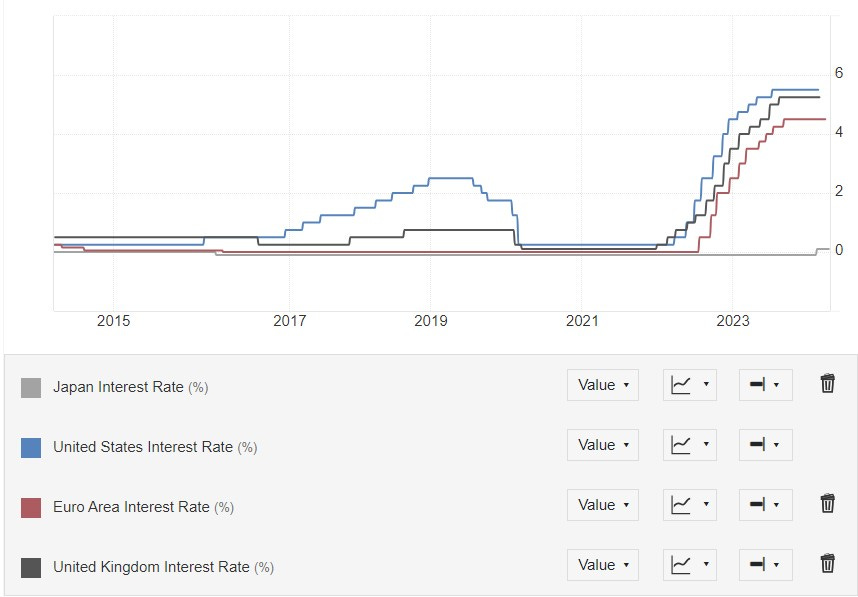

Carry Me

Two years ago, the Fed panicked and raised rates, and the ECB, BoE, and other Western central banks followed suit in the most aggressive rate hiking in history—but not Japan. As rates rose, a massive carry trade opened between the Yen and nearly every other currency, particularly the USD. The larger the rate spread, the more pressure built on their currency, and the Yen fell sharply.

Free Money for Warren

A carry trade is where you borrow a low-yielding currency to buy assets in a higher-yielding currency. With Japanese interest rates pinned at zero, borrowing Yen became free money when used to buy US Treasuries. Warren Buffett borrowed Yen to buy his massive position in the Japanese trading houses in 2021. Deutsche Bank analysts estimated that the Yen carry trade supported $20tn of overseas assets as of November last year, including $1.7tn of US Treasuries.

Defending the Indefensible

On two occasions over the last two years, the BoJ has used a total of $77bn of its dollar reserves to defend its currency, a short-term move that does nothing to solve the underlying structural problem. Last week, markets were left in expectation as the Yen weakened below its previous intervention level, but nothing came of it.

Project Zimbabwe

Tokyo’s policymakers must decide whether to let the Yen devalue further or use more of its dollar assets (Treasuries) to defend the currency. The former allows the carry trade to build further, making later adjustments more painful. The latter puts pressure on US 10-year yields and will likely strengthen the USD relative to the Yen it is trying to defend. Of course, with 263% debt to GDP and the BoJ owning more than half of all JGBs in issue, raising Yen interest rates risks a level of debt monetisation the equivalent of Zimbabwe or Venezuela. It is a position that a Victorian gentleman would recognise as being snookered.

Who's Next

The Federal Reserve of the United States will make its interest rate decision at its FOMC meeting this week, and the overwhelming expectation is that it will keep policy rates “higher for longer.” While its mandate includes preserving the integrity of the US money and banking system, it is not explicitly concerned with what happens in Tokyo or anywhere outside the USA—the clue is in the name. Japan cannot kick the Yen can down the road indefinitely it must start to close its interest rate gap; its plight is a foreboding lesson for all nations building unprecedented levels of debt in sluggish economies. Little wonder gold has reached new highs, now even for dollar-based investors.

Jeremy

Ealing

28/04/24