The Mansion House Accord - be careful what you wish for

The Pensions Investment Review is the thin end of an ugly wedge

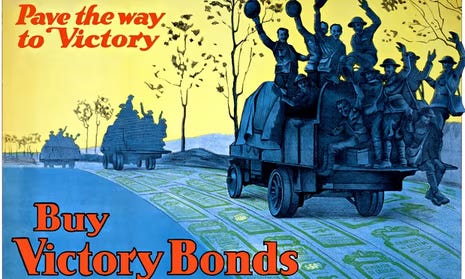

Frustrated and long-suffering investors and intermediaries in the UK stock market have been lobbying the government to take action. After all, what is more important to a growing economy than active and liquid capital markets? Specifically, it has been noted that the proportion of the UK's pension assets invested in its domestic stock market has declined significantly over recent decades.

Simon French at Panmure Liberum has done more than most in highlighting the extent to which the UK is a significant outlier in this regard and how it has made our equities cheaper than they otherwise would be, making them an attractive area for investment.

There is widespread agreement that action must be taken to directly address this evident impediment to achieving a thriving UK stock market, itself a precursor to economic growth.

Much hope and industry lobbying have been attached to an initiative known as the Mansion House Accord (MHA). These policy proposals, initiated by Jeremy Hunt, aimed to remedy this situation. It comprises a voluntary commitment by seventeen of the largest defined contribution pension providers to invest 10% of their main default funds in private markets, including 5% in the UK specifically.

While perhaps not sounding significant, the sums of money involved in the context of the UK's listed equity market are, in fact, meaningful. Estimates suggest that an additional £26 billion will be available to invest in AIM and Aquis by 2030, approximately 40% of their combined market value today.

Last week, the UK Treasury released its Pensions Investment Review, widely regarded as an opportunity for the government to demonstrate its commitment to the MHA initiative and broader commitment to the UK's capital markets, specifically by providing growth capital to smaller listed companies. In reality, there was little for UK market investors and its intermediaries to cheer about.

Neither of the Ministerial Forewards to the document mentioned listed equity markets. The MHA is mentioned in a descriptive appendix, while listed equity markets only feature in five bullet points, noting concerns but offering no new initiatives for action. The only fig leaf is the mention of a "reserve power", which would, if necessary, enable the government to set quantitative baseline targets for pension schemes to invest in a broader range of private assets, including in the UK, for the benefit of savers and the economy. A suitably vague set of objectives to cover most politically expedient bases.

This “reserve power” potentially represents the thin end of an ugly wedge. Why stop at equity investing when, having run out of other people’s money, it is clearly in the national interest from the perspective of the government of the day to buy UK gilts, for example?

The overwhelming body of the report focuses on the aggregation of local authority and other publicly funded pension schemes, their governance, reform and repurposing. It would appear that these measures are primarily aimed at improving funding for UK public infrastructure investments, in short, a brazen attempt to divert public employee pension assets towards political goals.

Meanwhile, the report fails to address the underlying factors that have led to the UK equity market's current position. Whether the risk neutering regulations imposed on UK pension funds after the Robert Maxwell Mirror Group scandal, Gordon Brown's attack on pension fund dividend income or the archaic levy of stamp duty on UK listed shares.

As Oliver Shah says in the Sunday Times:

Cutting stamp duty on shares, reinstating the dividend tax credit abolished in 1997, ending energy windfall taxes, lowering capital gains, reversing the inheritance tax raids on farms and family firms, and softening the assault on non-doms — a combination of any would start to improve the overall business environment. But each would cost money today, which is why we are ripping out kitchen sinks instead.

This Pensions Investment Review marks the first step toward financial repression, tied in a neat bow of doing what's best for us all. However, our world of rampant fiscal irresponsibility will not stop at such minor tinkering. This Review should be assessed in the context of an emerging global capital war; it prepares the ground for a full-scale assault on this country's pension assets. Other pools of assets will also be scrutinised. Consider yourself warned.

As a footnote, it is worth considering the government's approach to focusing on “improving” our funded pension schemes for the collective good, in contrast to its approach to ignoring our collective unfunded public pension liabilities.

As Dominic O’Connell points out in the Times this week,

Most of the big public pension schemes, [such as] the armed forces, the civil service, the NHS, are unfunded. There is no pool of assets. Instead, there is a government guarantee to pay what will be needed in the future. Current payments to retired staff are met out of contributions from this generation of workers, topped up as needed from taxpayer funds.

What effect does the promise to pay these future pensions have on the government’s finances? The total liabilities of all the public sector schemes are estimated at £1.4 trillion, but that number is not included in the £2.7 trillion national debt. It has always been deemed a “contingent” liability and so able to be excluded.

Adding in the pensions would take the UK’s debt-to-GDP ratio from 98 per cent to 150 per cent, an increase that would utterly swamp [Rachel Reeves’] fiscal rules. It has always suited chancellors to keep the public pension numbers tucked away out of sight, but their successors will, at some point, have to confront them.

And when they are forced to do so, it is likely to be the time when they come for your pension assets. Your country may not need you, but it does need your retirement savings.