The improbable life & death of Mike Lynch & the 250 year old secret that survives him

How the ideas of an English Enlightenment clergyman continue to change the course of history

Not everything that happens happens for a reason, but everything that survives survives for a reason: Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Skin in the Game, Hidden Asymmetries in Everyday Life.

I never knew Mike Lynch but followed him and the rise of Autonomy as a listed company. I never owned shares, nor was I ever professionally associated with him. I never had a dog in his many fights. However, his eulogies talk of a likeable, down to earth, family man with a passion for maths, science and engineering, all commendable qualities. Following last week's tragic events in Sicily, I feel a visceral sense of loss for what might have been.

As with many successful entrepreneurs, Lynch didn't shy away from controversy. As is often the case, he thrived on it. He was unafraid to be different and was prepared to aggressively defend himself during periods of adversity.

What made him act in this way? Was he just an arrogant, sociopathic, narcissistic tech CEO of common belief? I cannot be sure, but I suspect there is a better explanation.

Lynch knew a secret about the world that most others didn't. It was an idea with roots stretching back two hundred and fifty years to a clergyman of the English Enlightenment. Lynch was convinced this idea's time had come, and his relentless pursuit of what Ben Hunt might describe as uncommon knowledge made him very rich and unpopular.

In his book Zero to One: Notes on Start Ups, or How to Build the Future, Peter Thiel, who is also rich and unpopular, said

People are scared of secrets because they are scared of being wrong. By definition, a secret hasn't been vetted by the mainstream. If your goal is to never make a mistake in your life, you shouldn't look for secrets. The prospect of being lonely but right—dedicating your life to something that no one else believes in—is already hard. The prospect of being lonely and wrong can be unbearable.

What made it worse for Lynch’s critics was that he was very right about the potential implications of Bayesian inference.

Thomas Bayes was a nonconformist preacher and mathematician who, late in life, became interested in the work of a French Huguenot immigrant, Abraham de Moivre, and his book, The Doctrine of Chances. Following his death, Bayes left his workings to a fellow nonconformist preacher and mathematician, Richard Price.

In 1763, Price presented what became known as Bayes' Theorem to the Royal Society, based on Bayes' Essay Towards Solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances. Price applied Bayes' ideas to understanding life expectancy via his work with The Society for Equitable Assurances, becoming a founding father of actuarial science.

Bayes' powerful and radical theorem could compute inverted conditional probability, calculating the probable cause of an event given its effect. It later allowed what became known as Bayesian inference, enabling comparing prior knowledge with measurable events and probabilistically arriving at posterior knowledge.

Those still following will notice that Bayes' work formed a learning model. Bayesian inference became the bedrock of generative AI (GAI) and large language models (LLMs), ideas that have recently and dramatically become common knowledge.

Lynch realised while working on a PhD in artificial neural networks in Cambridge during the 1980s that rapidly increasing computational power was likely to make the application of Bayesian inference a ground-breaking technological breakthrough with significant commercial potential. After a few false starts, he used this secret idea to drive Autonomy to become a FTSE 100 company, personally becoming a billionaire.

In the context of the UK adult population, there is about a 0.0005% chance of being a billionaire. By any standards, a remote and highly improbable outcome. Ironically, there is a similar probability for a UK adult to die from drowning. We could, of course, infer the precise probability of a UK billionaire dying of drowning, but suffice it to say, in common parlance, it approximates zero. The point is that risk and luck are the opposite sides of the same coin. During Lynch's extraordinarily improbable life, he experienced each end of humanity's long tail of potential outcomes.

Lynch was frequently referred to as the UK's Bill Gates. In his epic book The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness, Morgan Housel brilliantly portrayed the realistic but contrasting narratives of Bill Gates and his high school friend and computer club co-founder, Kent Evans. Housel estimated that each experienced a 1-in-1-million event before reaching adulthood. For Bill, attending a high school with a mini-computer in the early 1970s was a 1-in-a-million stroke of good luck. There, he, Bill Allen and Kent Evans famously wrote a programme that solved their school's timetabling problem, setting the scene for Gates and Allen to set up Microsoft and become billionaires. A few months later, their friend Kent died in a 1-in-a-million climbing accident.

Housel explains

Luck and risk are so similar that you can't believe in one without equally respecting the other. They both happen because the world is too complex to allow 100% of your actions to dictate 100% of your outcomes. They are driven by the same thing: You are one person in a game with seven billion other people and infinite moving parts. The accidental impact of actions outside of your control can be more consequential than the ones you consciously take.

According to Nassim Nicholas Taleb, a former options trader turned public intellectual and prolific writer on risk and uncertainty, we are fooled by life's randomness. We try to rationalise outcomes via back-fitting narratives and explanations. It is our evolved way of coping with the scary world and the overwhelming odds stacked against our very existence, let alone our path to success.

For Taleb, this self-deception makes us overestimate our ability to predict the future and determine its outcomes. This message does not endear Taleb to those who imagine the world as fully explained and managed by quantitative models of mechanistic certainty, such as those used by economists, policymakers, and central bankers.

Last week, the West's monetary policy wonks gathered at their annual marshmallow roast against the backdrop of the majestic Grand Tetons. Their mission was to opine on their deterministic econometric models and their consequential ability to execute the widely hoped-for soft landing.

It was good news. Everything investors and markets were hoping for was delivered. In his speech, Fed Chair Powell made his strongest statement yet about his confidence in the future downward trajectory of the Fed Funds Rate. Better late than never, but make no mistake, the Fed Put is in, and markets are safe from the dreaded hard landing and associated market risks and uncertainties.

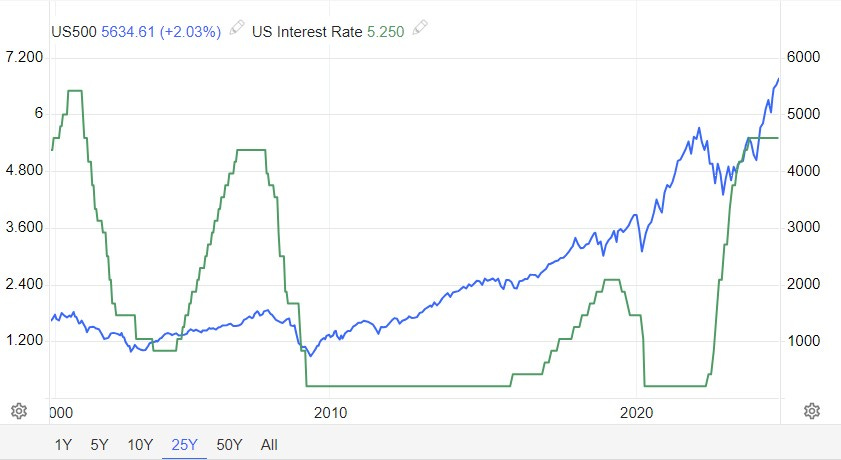

However, looking at stock market history suggests an alternative inference to this prescribed positive narrative. The three previous periods of rate cutting were followed by significant economic weakness and market correction. The Fed last initiated rate-cutting cycles in November 2000, June 2007, and October 2019, and within a year, the S&P 500 had an average drawdown of over 40%.

Is this relationship statistically significant, and if so, what can investors infer from it?

For Housel, everything will be OK in the long term, so why worry?

The historical odds of making money in US markets are c50/50 over one-day periods, 68% in one-year periods, 88% in 10-year periods, and (so far) 100% in 20-year periods.

As he says

The S&P 500 is up 154-fold over the last 50 years and my guess is the majority of investors thought it was overvalued the majority of the time.

For Taleb, only by having skin in the game can we fully understand risk, react to its infinite randomness and adapt to remain in the game; the critical success factor is resilience or antifragility. For him,

Probability is not a mere computation of odds on the dice or more complicated variants; it is the acceptance of the lack of certainty in our knowledge and the development of methods for dealing with our ignorance.

Taleb’s human world is driven by its abnormalities, allowing us to solve for our ignorance and the forces aligned to take us out of the game. Sadly, Mike Lynch didn't make it—an improbably tragic loss at a moment when his life seemed destined to offer so much more.

But the world has started to understand and embrace what was once his secret, which has since become more common knowledge. We can take some comfort from the fact that Lynch's valuable ideas and achievements have survived him for good reason. We must now hope that others can take up the challenge.

The final word to Peter Thiel,

The actual truth is that there are many more secrets left to find, but they will yield only to relentless searchers. There is more to do in science, medicine, engineering, and in technology of all kinds. We are within reach not just of marginal goals set at the competitive edge of today's conventional disciplines but of ambitions so great that even the boldest minds of the Scientific Revolution hesitated to announce them directly. We could cure cancer, dementia, and all the diseases of age and metabolic decay. We can find new ways to generate energy that free the world from conflict over fossil fuels. We can invent faster ways to travel from place to place over the surface of the planet; we can even learn how to escape it entirely and settle new frontiers. But we will never learn any of these secrets unless we demand to know them and force ourselves to look.