Shifty Vibes & Paradigms

The forces that politicians tried to forget and bury forty years ago & why all roads lead to real assets.

Crisis exists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum, a great variety of morbid symptoms appear. Antonio Gramsci, Prison Notebooks, 1929.

This week, I watched Adam Curtis’s recently released series, Shifty, which documents the UK’s social and cultural condition before the advent of the internet. It is five hours of thought-provoking and compelling television, exploring the roots of the world we inhabit today. Curtis has much in common with the great historical cultural commentators, such as Dickens, Marx or Gramsci; one does not have to agree with them to appreciate their analytical significance.

In Shifty, Curtis adds a fascinating critique of the UK during the last three decades of the 20th century to his other notable topics, such as the brilliant 2022, seven-part Trauma Zone series, which covered the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia’s failed attempt at Western democracy, and the rise of Putin.

I first became absorbed by Curtis when he released the 2011 series, All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace, based on the 1967 countercultural poem of the same name. However, I was blown away by his 2016 film HyperNormalisation, which the BBC describes as follows:

We live in a time of great uncertainty and confusion. Events keep happening that seem inexplicable and out of control. Donald Trump, Brexit, the War in Syria, the endless migrant crisis, random bomb attacks. And those who are supposed to be in power are paralysed - they have no idea what to do.

This film is the epic story of how we got to this strange place. It explains not only why these chaotic events are happening - but also why we, and our politicians, cannot understand them.

It shows that what has happened is that all of us in the West - not just the politicians and the journalists and the experts, but we ourselves - have retreated into a simplified, and often completely fake version of the world. But because it is all around us we accept it as normal.

I continue to believe we live in a world of hypernormality, hence the name of this blog. As the BBC concluded, Curtis’s hypernormal thesis has profound and continuing relevance today:

There is another world outside. Forces that politicians tried to forget and bury forty years ago - that then festered and mutated - but which are now turning on us with a vengeful fury. Piercing through the wall of our fake world.

While HyperNormalTimes’ focus is on the economy and financial markets, it is necessary to contextualise developments in these areas within the social, cultural, and political spheres. (Which lives downstream of the other is an interesting diversion that I won’t take). However, these spheres are colliding and influencing each other in increasingly profound ways, with unexpected outcomes. We live in humanity’s very own three-body problem.

Here’s the thing: the chaotic outcomes of today’s world cannot be understood by people operating full-time in the normie worlds of regulated finance, mainstream media, and politics. Notably, Curtis’s work appears on the BBC iPlayer; indeed, his work depends on the BBC archive for its production, but his output is rarely broadcast and hardly ever promoted there.

After all, Upton Sinclair told us that:

A man will not believe something that his livelihood depends on his not believing.

Similarly, for various reasons, regulated financial services businesses tend to avoid detailed social, cultural, or political critique in their analysis of financial markets. Over recent years, this gap has been filled by independent analysts and commentators, each with their own take on what the BBC called the forces that politicians tried to forget and bury forty years ago, but which are now turning on us with a vengeful fury.

The content creators I rate who have successfully navigated this opportunity in the market for ideas include Lyn Alden, Grant Williams, Neil Howe, Russell Napier, Luke Gromen, Doomberg, Dominic Frisby, Adam Taggart and Hugh Hendry. Of course, none of these have all of the answers, but they are all able to ask critical questions.

And as Richard Feynman said:

I would rather ask questions I cannot answer than have answers that I cannot question.

In the context of traditionally regulated finance, these questions have included the very nature of how we measure value, specifically our money and its core collateral asset, the sovereign bond, exemplified by the US Dollar and US Treasuries.

One investor and writer, who has bravely stood aside from the mainstream finance operators, whom David Dredge calls Rational Accounting Man, is wealth manager Tim Price of Price Value Partners. Tim told me last year that anyone investing in government bonds was dancing around the edge of a live volcano. Still, if they must go to the party, they should only dabble in short-duration paper, enjoy themselves, and dance near the door.

Tim has brilliantly written a comparison of the Aberfan tragedy, as described by former BBC journalist John Humphreys, with the rising and uncontrolled levels of sovereign debt in the Western world. In a distressing account of the preventable tragedy in October 1966, which killed 116 children and 28 adults, Tim concluded his piece by saying:

The Aberfan tragedy was avoidable. It was certainly forecastable. The ultimate demise of the mountain of debt that overshadows all of us, and for that matter the next generation who will inherit it (or live with the aftermath of its cancellation, or being inflated away) is just as forecastable, if not necessarily easy to time. In this regard, in taking specific and meaningful action to protect one’s wealth and valuable capital, better even a year too soon than just a minute too late.

I am now going to say the quiet bit out loud. This system of fiat currencies and their regulated IOUs is following the same path as all fiat currencies have before in the entire known history of fiat currencies. They are tending to what they are worth. That is to say, nothing. The only debate now is at what rate and in what order the 180 currencies in the world today will implode.

This is the financial system’s fundamental three-body problem. Financial markets and the investment environment are undergoing profound change. I have been raising the following issues and exploring some of their most significant implications over the past five years: Fiscal policy now dominates monetary policy; inflation has become more difficult to contain with traditional policy tools; central bank independence is being openly questioned; de-globalisation has raised the prospect of international trade wars and global capital wars; finance ministers of over-indebted nations are increasingly asking, "Who is going to buy my bonds?"

The strategic investment implications of these trends are that government bonds no longer provide effective risk mitigation for investors. There is increasing evidence of the broader adoption of real assets by major financial institutions and government organisations. Gold has become the fastest-growing reserve asset for nation-states. There is political pressure from Italy and Germany to take physical delivery of their sovereign bullion from the US. (Sadly, thanks to Gordon Brown, the UK no longer has a dog in this fight). Spot markets for silver and platinum are being stressed by investors seeking physical delivery rather than accepting paper settlement.

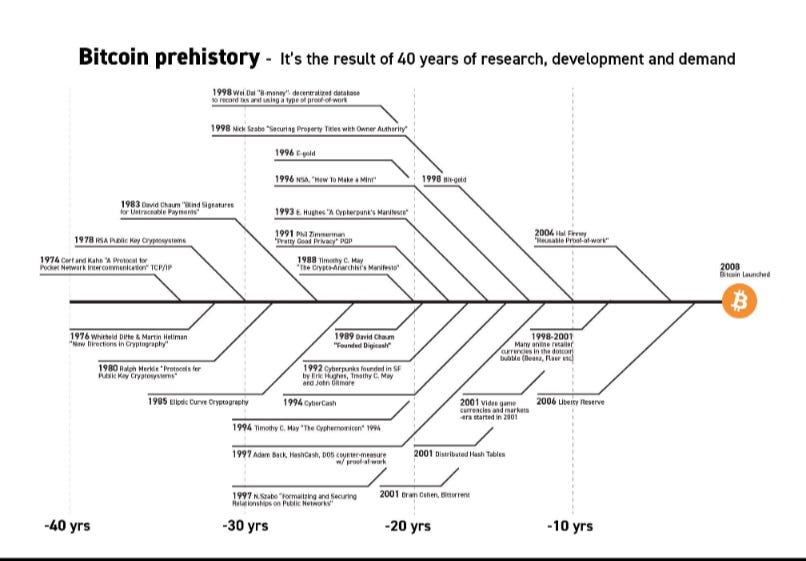

Individual investors, corporations, ETF providers, and now national governments are adopting Bitcoin. In our increasingly hypernormal existence, it is evident that Bitcoin has established a position as a legitimate means of wealth preservation and value exchange alongside precious metals.

As I said in May:

Investors need an escape valve, and the Buck finally stops with the US dollar. A new form of capital preservation is necessary, one that is politically neutral and not the liability of anyone else: gold and Bitcoin fit the bill.

Follow Mrs Wantanabe to the Escape Valve

Over the next decade, we expect larger deficits as entitlement spending rises while government revenue remains broadly flat. In turn, persistent, large fiscal deficits will drive the government's debt and interest burden higher. The US' fiscal performance is likely to deteriorate relative to its own past and compared to othe…