Niccolo Machiavelli, the unsung father of political philosophy in the Italian Renaissance, knew that politics involved deception, treachery, and crime. A student of what political people did, not what they said, he assessed that politics is about man's struggle for power and its ideological baggage, just a cloak.

As he explained in Discourses,

the value of religion lies in its contribution to social order, and the rules of morality must be dispensed with if security requires it. Having a religion is, in any case, essential to keeping a republic in order.

However, for Machiavelli, a great prince

can never be conventionally religious himself, but he should make his people religious if he can.

Further, he needs to argue that good ends justify bad things. You can fill in the new religions of your choice at this point.

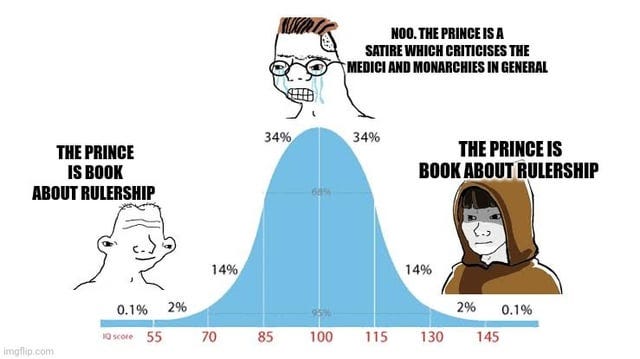

Machiavelli, who worked for those who opposed the Medici family, knew that the powerful elites did not welcome his ideas, and his seminal work, The Prince, was not published until five years after his death. Unlike his Italian Renaissance contemporaries, Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Copernicus, Machiavelli's influence has not been widely recognised by modern thinkers and educators. Indeed, the fact that Stalin kept a personally annotated copy of The Prince and that 'Old Nick' became a term for the Devil is testament to Machiavelli's enduring but infamous impact on our political heritage.

Amidst a year of 64 elections involving nearly half of the global population, Machiavelli's insights are resurfacing with renewed relevance. The traditional political dichotomy of Left and Right is proving inadequate to mask the Machiavellian truth that politics is fundamentally about acquiring and maintaining power, a reality being effectively exploited by emerging nationalist and populist movements worldwide.

In a recent article in the Sunday Times, Matthew Syed bemoans the political class's lack of backbone and frontline politicians' readiness to follow the path of least ideological resistance in their quest for power. Syed's critique extends beyond the senior ranks of the Labour Party, highlighting a broader issue that transcends party lines and national borders.

He says,

In many ways, it is a summary of much of what has gone wrong with Western culture in the social media age: free speech has been replaced by fear of cancellation and groupthink. Is it any surprise, then, that when we hit peak trans activism, they started to obediently spout the ideology of the dominant group, like Red Guards, during the Cultural Revolution? I worry that a future Labour government will genuflect before any campaign with sufficient momentum. I mean, look at the sheer scale of Starmer's flip-flopping, not just on trans issues but the nationalisation of trains, renewable energy, tuition fees, Diane Abbott and, just last week, the definition of "working people". What is his true position, his moral centre of gravity? And this is important because we live in a world of increasing moral activism, a world where unrepresentative minorities are ever more determined to get their way.

Syed's concern is a microcosm of electorates everywhere who can see their established politicians' inherent duplicity and spineless lack of conviction; that is why outsiders are gaining ground in nearly all contests, flushing out ruling parties. Nowhere is this more apparent than in nationalism and geopolitics, two of Machiavelli's strongest suits.

As he was well aware, features common to all nation-states are their monopoly on violence and money and, specifically, the use of one to enforce the other. In times of low inflationary growth, relatively full employment, and rising real incomes, such as those enjoyed since WW2, Western democracies can shield their electorates from the harsh reality of their political authority. That was then, but this is now.

Today, outdated ideologies are being exposed as the world deglobalises, becoming more inward-looking, indebted, and dangerous. This creates the political space for opportunists without ideological baggage but a shopping list of grievances. Such grievances resonate with electorates, especially when packaged as a subgenre of the entertainment industry.

Voters are disillusioned with being told they have never had it so good, followed by a bombardment of how bad things would be if the outsiders were allowed in. Established political parties haven't been this unpopular in living memory, and our overproduced elites remain in denial about the reasons why. Old Nick knew.

Jeremy