NatWest or Nakamoto?

The process by which banks create money is so simple that the mind is repelled. JK Galbraith

Bitcoin will do to banks what email did to the postal industry. Rick Falkvinge

The advent of the internet seeded the evolution of digital money; free and instantaneous information exchange demanded frictionless payment rails. Cryptographically secure forms of money independent of third-party verification, so-called trustless money, became the goal. Early attempts such as Beenz.com, digicash, digigold, and cybercash failed the acceptance test, becoming Darwinian dead ends.

Then, in late October 2008, a few weeks after the Lehman Brothers collapse, Satoshi Nakamoto emailed a short paper entitled Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System to a circulation list of cryptographers and cypherpunks. After some amendments, Satoshi published the Genesis Block on the Blockchain ledger in January of the following year, referencing a newspaper article, “The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.” Nine days later, Hal Finney received the first recorded Bitcoin transfer with the gift of 10 Bitcoin from Nakamoto.

Ten months later, in October 2009, the first recorded exchange transaction occurred among BitcoinTalk forum members, with 5,050 Bitcoins changing hands for $5.02 via PayPal. The buyers had paid just under one US Cent per coin. Laszlo Hanyecz infamously bought two Papa John’s pizzas for 10,000 Bitcoin the following May, becoming the first person to engage in a commercial Bitcoin transaction. Each pizza cost him $250,000 at today’s exchange rate.

As the first trustless money life-form stuck its head out of the pre-Cambrian swamp and drew breath, the dinosaurs roaming the upper reaches of the known World of fiat money and fractional reserve banking were having their meteor moment. Among the old order, choking to death on a lethal cocktail of toxic assets supported by Ponzi-type financing structures was the gargantuan British bank, then called Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), regulated by the FSA and overseen by the Bank of England, today known as NatWest.

If Adam Smith’s Men of System had failed at this point to “act in the public interest” by dosing the banking system with hundreds of billions of dollars of taxpayer’s money and doing whatever it took to socialise the clean-up cost of the few by the many, this moment could have been wonderfully Schumpeterian. As it was, the “Men of System” decided they had to save their right to print money, fiat money, and the banks that survived off its central direction were bailed out. But, there was a grand bargain, and banking would never be the same again. The banks became enslaved to their political masters, bound by regulation and fines for all past and present bad behaviours and misdemeanours. The price for which is still being borne by bank shareholders nearly two decades later, car finance mis-selling, is just the latest iteration.

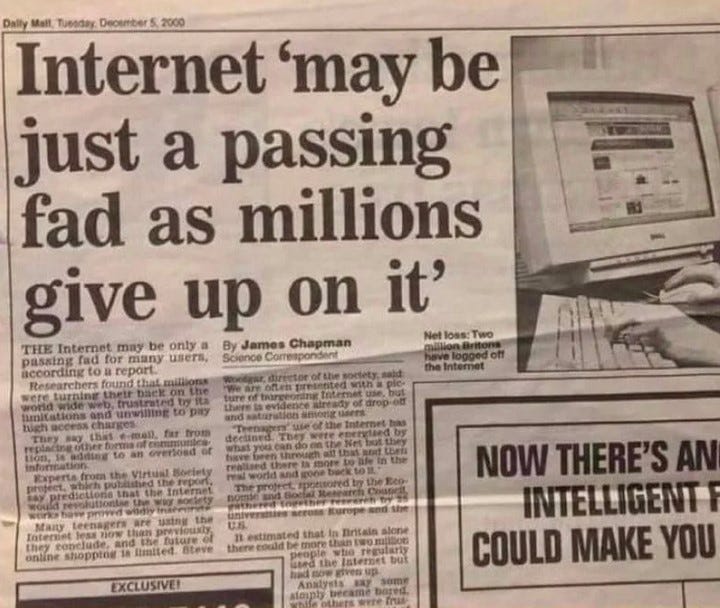

No known use case [Daily Mail, 2000]

Meanwhile, Bitcoin grew; there were setbacks, but the network adoption of its distributed ledger grew faster than the internet twenty years before. Like the internet in the 1990s, Bitcoin has been dismissed as a hobby interest without a use case and with subversive connotations. Yet, the Bitcoin network demonstrates antifragile qualities. It came back stronger after each setback, and by 2013, afer its first halving, the price was moving in the $200-$1,000 range.

That year, the Winklevoss twins, Harvard contemporaries of Mark Zuckerberg, applied to the US Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) to register the first Bitcoin Exchange Traded Fund (ETF), starting a ten-year battle of increasing intensity joined by ever more mainstream financial services companies for a low cost regulated means for investors to gain access to this emerging asset.

Last month, the SEC finally consented to register eleven Bitcoin ETFs for the first time. The SEC’s blocking actions of the previous decade had “saved” investors, whom it is mandated to protect, from a 100-fold return opportunity. The swamp creature had reached official recognition. As Gandhi said, First they ignore you, then they ridicule you, then they fight you, and then you win.

As Bitcoin overcame adversity to regulated acceptance, things at NatWest were not so good. Since the GFC, NatWest has lost 75% of its market value. Its shares are 30% lower than they were a decade ago. As a majority-owned government entity, the bank became more interested in social policy than the interests of its customers. It proudly refused to lend against profitable hydrocarbon assets and de-banked undesirable people, practices backed by the Board.

We recently learned that the Treasury plans a “Tell Sid” campaign to sell its remaining holding in NatWest to retail investors, raising several questions. First, don’t we, the country’s taxpayers, already own it? Second, should most private investors hold individual shares, particularly in banks? Third, isn’t this just a cynical attempt for a government to rid itself of a problem?

While we are repeatedly told past performance is not a guide to the future, we instinctively know this statement for what it is: regulated arse-covering. Based on the evidence of the last 15 years, I prefer to own Bitcoin than shares in NatWest. This is not investment advice; it is just what I will do.

As we approach Bitcoin’s next halving event in April, with wealth managers and financial advisors initiating small allocations from their client portfolios into the most incorruptible, non-inflationary asset class ever known, Bitcoin’s historic compound annual growth rate might yet be a conservative guide to its future returns. What you can be sure of is that it won’t develop a political agenda along the way.

Jeremy

The post NatWest or Nakamoto? appeared first on Progressive.