Restrictive the New Transitory

The ECB and The Bank of Canada have started the long-anticipated rate-cutting cycle in the West’s major economies. However, they both did so with a forewarning that their new interest rate levels remain restrictive and disinflationary. This allowed them to reassert the pretence that central bankers can fine-tune economic outcomes and affect a soft landing. (Notably, as it trimmed 25 bps from its policy rate, the ECB revised its forecast for inflation upwards). The Bank of England would follow this established central bank narrative at this Thursday’s MPC meeting if it weren't for the General Election, as will the Federal Reserve whenever it cuts rates in due course.

Fed Reassurance

Continued mixed messaging about the US economy’s performance casts doubt on the timing of the Fed's first rate cut decision. Fortunately, Fed Chair Powell helped investors at last week's FOMC presser by indicating that while its collective wisdom only sees scope for one rate cut this year, most likely in November, the median of the June 2024 Fed dot plot projects Fed Funds to fall 100 basis points in 2025, and 100 basis points in 2026, for a total of 225 basis points reduction over the next 36 months.

No Idea

However, if you look under the hood, by the end of next year, just 18 months from now, the spread of dots plotted by the FOMC members ranges from 5.25% down to 2.75%. This wide difference of view among the US supreme monetary authority members results from a wider-than-normal gap between the performance of different sectors, mirroring the gap between tight monetary policy and loose fiscal policy. We have previously compared this policy mix to driving with one foot on the brake and the other on the accelerator.

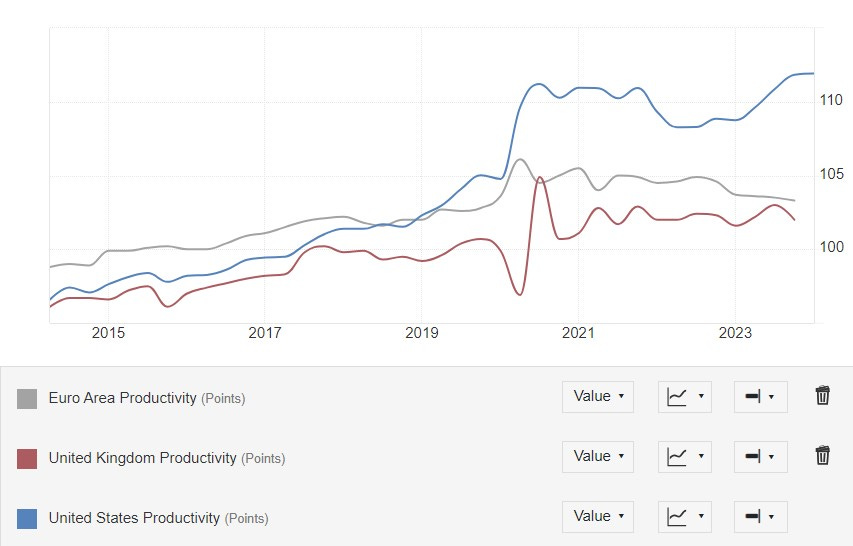

US Exceptionalism

However ill-conceived this policy mix sounds, it has delivered a period of superior US economic growth compared to the EU and the UK, further enhanced by its access to cheap domestically produced energy in the form of natural gas and shale oil. As Matthew Syed identifies in his weekly Sunday Times column,

abundant energy sits at the centre of all economic activity and, therefore, growth … The point is that productivity growth is about energy, energy and energy. And, while economists fiddle with their abstract models, this is what is screwing us today: we are an energy-constrained civilisation … productivity will rise only when we move to higher-EROI sources of energy. Everything else is whistling in the wind … the UK should be rapidly building a fleet of nuclear power stations.

Once you factor in AI's looming energy appetite, the case for an energy-abundant future becomes even more compelling.

Wishcasting

Last week, the International Energy Agency issued its official 2030 oil forecast, triggering many anxious headlines such as this from the FT, World faces ‘staggering’ oil glut by end of decade, energy watchdog warns. How could this be when energy is the lifeblood of our economic health, and our ability to harness it in increasing quantity underpins our very existence and is something the US excels at?

The world faces a ‘staggering’ surplus of oil equating to millions of barrels a day by the end of the decade, as oil companies increase production, undermining the ability of Opec+ to manage crude prices, the International Energy Agency has warned. While demand is forecast to peak before 2030, continued investment by oil producers, led by the US, would by then result in more than 8mn b/d of spare capacity, the IEA wrote in its annual report on the industry released on Wednesday.

End Not Nigh

Predictions for the world reaching peak oil date back to twenty years after the first commercial oil well was sunk, in 1859, and until a few years ago, it was always about the world having reached a peak in crude oil supply as all the big reserves had supposedly been discovered. Such views ignored the invaluable and counterintuitive lesson from the late economist Julian Simon in his book, The Ultimate Resource, encapsulated by Dylan Grice’s meme that If you are long commodities, you are short human innovation and before that by Saudi Arabia’s first Oil minister, Ahmed Yamani saying that the stone age didn’t end because we ran out of stones.

Peak Irony

As blogger Doomberg points out, all primary energy resources are additive to human endeavour, which principally involves a constant, unrelenting struggle against the forces of entropy. Doomberg’s Postulate™ states:

Every molecule of fossil fuel produced worldwide will be burned by somebody somewhere, and local efforts to restrict consumption merely relocate the enjoyment of that privilege.

In other words, every drop of oil produced will be consumed, as attempts to sanction Russian oil have shown. To put this statement into context, as of the end of last year, the world has yet to reach peak coal demand, and in some areas of the world, the demand for firewood remains at all-time highs. We are closer to peak irony than peak oil. As Doomberg speculates,

Will the price of oil go up from where it trades today, or will it go down? The answer is yes. It will do both. When it accelerates upward, demand pulls back and new supply investments are made.

This is a simple but obvious statement about how markets work. Yet, the IEA and its economist, Executive Director Fatih Birol, overlook this reality in favour of the IEA's’ increasingly partisan and anti-fossil fuel rhetoric.

Cheaper Energy

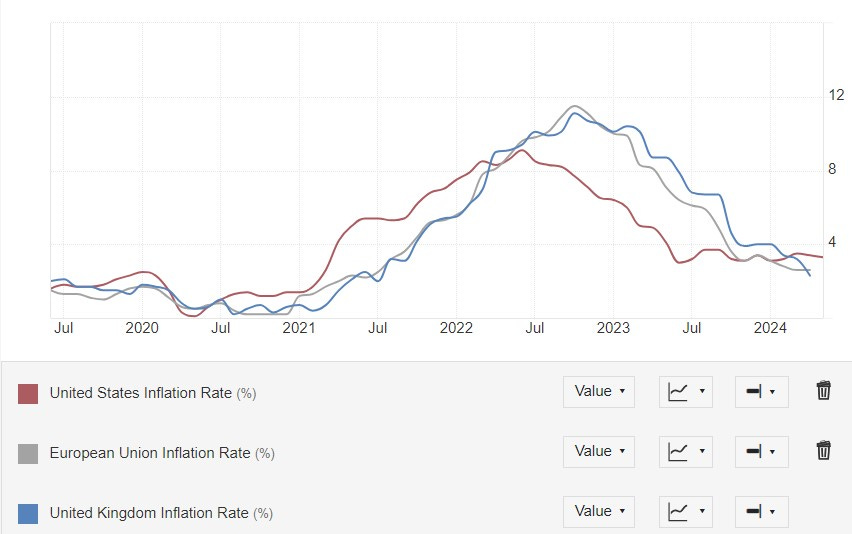

However, whatever the long-term demand-supply conditions for oil are, the short-term direction of oil prices and the broader energy complex have been negative. This has been a significant tailwind to the taming of inflation, and nowhere has this factor been more impactful than in the UK.

Thanks, Liz

The Truss debacle in 2022, currently being replayed in election campaigning as a failed attempt at unfunded tax cuts, was, in fact, more of an ill-fated effort to underwrite the UK economy from the impact of spiralling energy costs. The immediate result was for the Sunak/Hunt unity team to burden the UK with higher for more extended energy costs as global prices began to stabilise in 2023. However, UK energy costs have recently fallen faster than in the EU or US. As the chart above shows, the UK’s energy inflation is now materially below that of the US and the EU.

UK Inflation Trends to Target

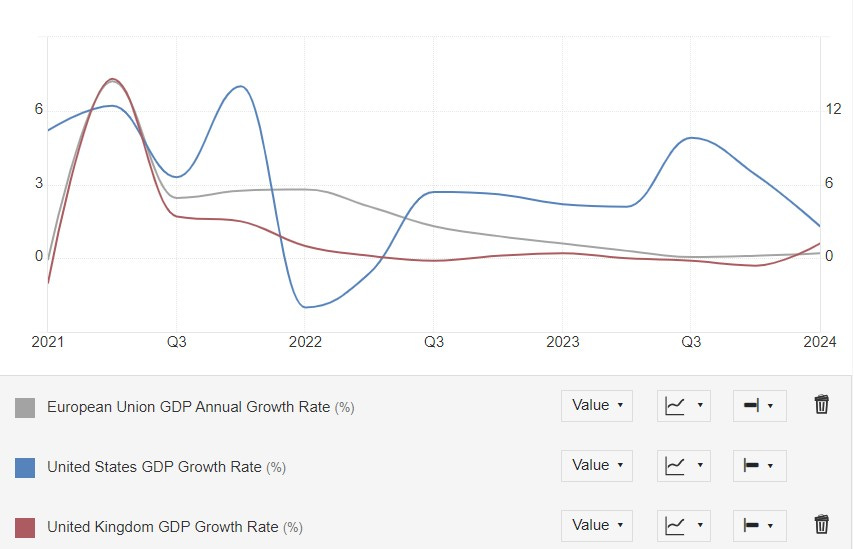

On Wednesday this week, the UK could become the first major Western economy to reveal an annual inflation rate at or below the generally accepted target of 2% pa. Yes, the UK rate is the blue line above. This coincides with the UK’s annual GDP growth (the red line below), which is doing better than expected. At the same time, the US growth rate decelerates, and Europe faces increasing politically induced financial market volatility.

Political Vol

After last weekend’s surprise snap French National Assembly election, the French bond premium blew out to a level not seen since Brexit, albeit below those seen during the Euro Crisis. However, as Mike Howell at Cross Border Capital points out, increased asset price volatility reduces collateral lending rates and balance sheet capacity for financial intermediaries, reducing liquidity.

The EU is confronting a radically changing order that could, in Barry Norris's view, see the end of net zero and the EU,

After the month-end, we saw parliamentary election results that significantly weakened President Macron in France and Chancellor Schultz in Germany. The success of European elections for parties termed populist or far right by the sneering classes but who articulate the growing frustration of culturally Marxist ideologies, whether that be wokeism, climate change alarmism, or immigrationism, all of these perceived to undermine standards of living and national identity. There is a risk that this political backlash within the EU is underestimated. Calling early parliamentary elections, President Macron may also be underestimating the seriousness of the situation. It is quite possible that we are seeing the beginning of the end for both Net Zero and the EU.

Carrying On

The UK’s political course is comparatively secure and already priced in by financial markets. Although the UK has many issues, its assets are demonstrably cheaper and less risky than those of other markets available to global investors, which typically have similar levels of growth but with more political uncertainty.

As Emma Duncan recently wrote in the Times,

If Britain were a stock, I’d buy: the price is low, the fundamentals are good and the quality of governance is bound to rise after the election … What Britain needs is investment, and what investors need is stability. That’s precisely what has been lacking for the past decade. Business investment as a share of GDP stalled in 2016, while it continued on its normal trajectory elsewhere in the world. Uncertainty, as much as Brexit, explains Britain’s underperformance.