with Howard Marks, Thomas Sowell, Friedrich Hayek & Cliff Asness

The price system is just one of those formations which man has learned to use (though he is still very far from having learned to make the best use of it) after he had stumbled upon it without understanding it. Thomas Sowell.

I consider the Britpop era a consolation prize for enduring the first Blair government. I enjoyed the music of the Gallagher brothers, The Stone Roses and Damian Albarn mainly because they epitomised Britain's creative flair in a music industry, too often characterised by the conventional beat of North American output.

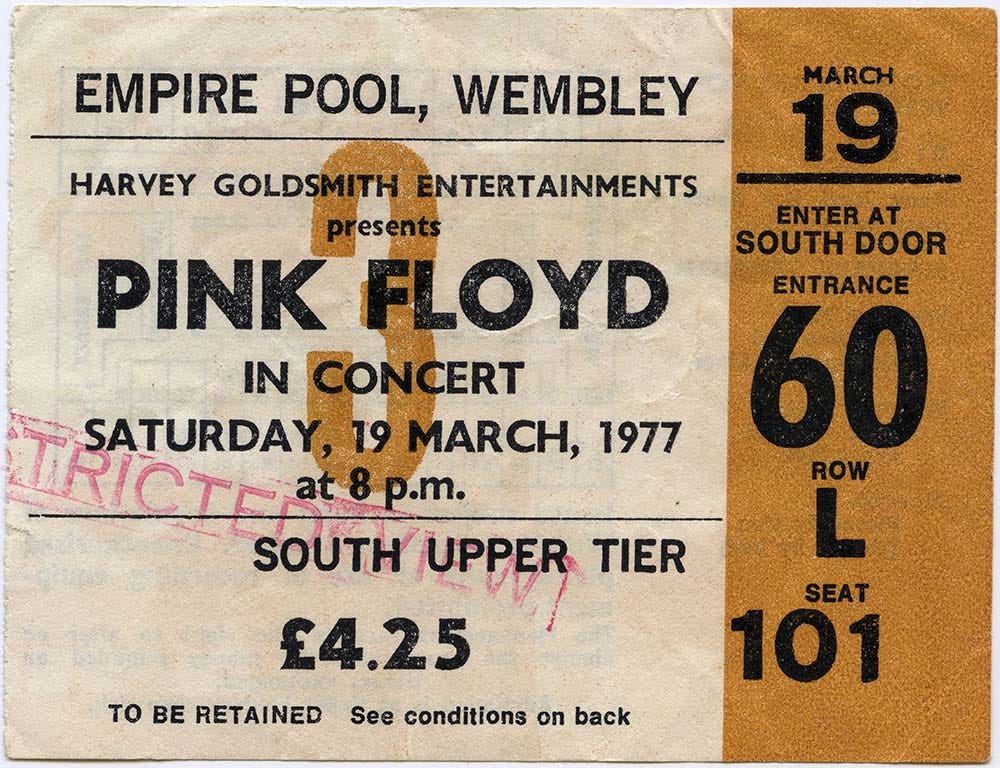

News of the Oasis Live '25 Tour didn't stir me to investigate the likely prohibitive cost of seeing them perform. Still, I understand the motivations of many who were prepared to jump through the inevitable hoops to secure tickets. Having seen Pink Floyd, Bruce Springsteen, Elvis Costello, and Talking Heads perform in their prime, I feel secure that whatever Oasis reformed manages to replicate, it won't meet my high bar of past greatness.

Of course, my decision was framed by the near certainty that whatever the cost (pecuniary and non-pecuniary), it would exceed the value of those tickets in terms of the alternative options I might have for the amount of money and time I would be required to forfeit. Sounds simple, doesn't it?

However, the outrage of politicians who increasingly see prices as normative (good or bad) and increasing prices as prima facie evidence of market abuse or failure disappointed even my low expectation of the declining economic literacy of the political class. I sometimes prefer not to think of our politicians as uneducated as they make out; I am tempted to think of their behaviour as a more performative reflexive concern for any available victim group. However, I don't know which explanation is the greater worry.

Andrew Lilico reported in The Spectator:

Sir Keir Starmer has said he is looking at 'a number of things' to reduce concert prices and that 'we'll grip this and make sure that tickets are available at a price that people can actually afford.' At the same time, Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson wants to stop airlines from raising prices during school holidays.

Recently, legendary investor and memo writer Howard Marks asked if we should repeal economic reality, propounding:

Politicians can promise whatever they want regarding the economy, but they won't be able to deliver if their promises fly in the face of economic reality because, ultimately, the laws of economics are incontrovertible.

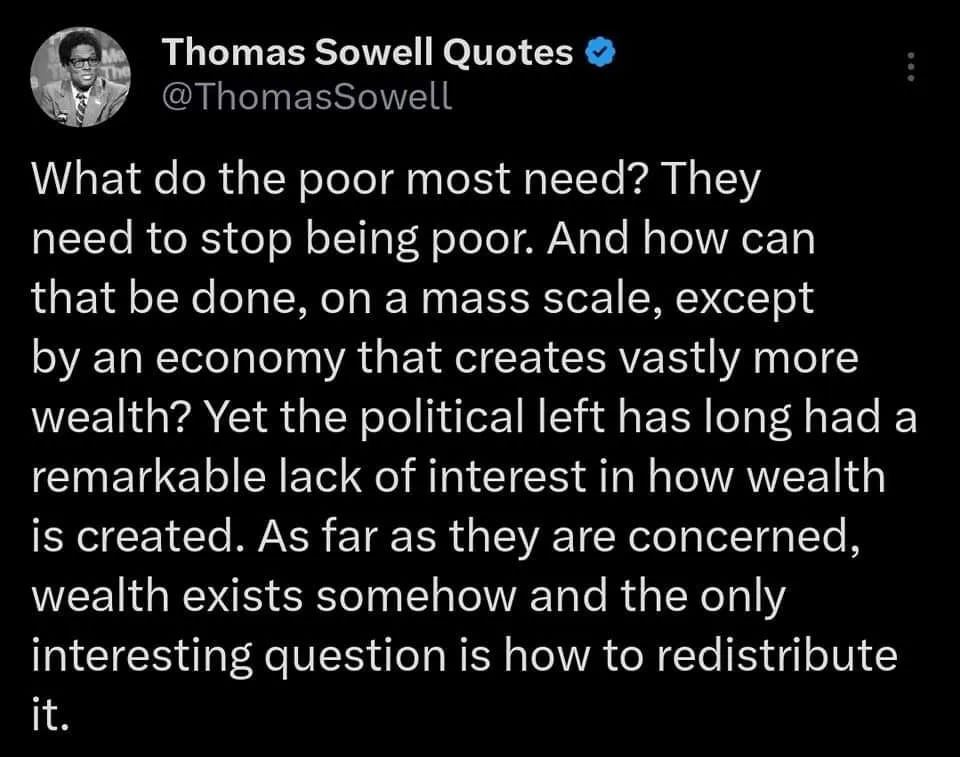

Thomas Sowell, arguably the most under-rated economist and social commentator alive today, put it:

The first lesson of economics is scarcity: there is never enough of anything to fully satisfy all those who want it. The first lesson of politics is to disregard the first lesson of economics.

Economic reality is often hard, a fact that does not go away when so wished, even by popularly elected politicians on mandates to correct for life's perceived inequities.

Economics branded the dismal science, understands scarcity and trade-offs. Resource constraints bound our desires, motivating us to innovate to satisfy existing desires and understand new ones. Human progress from early self-sufficiency to today's highly sophisticated, interconnected modern economy stems from our ability to harness knowledge in pursuit of solving the economic problem.

Sowell explains:

Cavemen had the same natural resources at their disposal as we have today. The difference between their standard of living and ours is the difference between the knowledge they could bring to bear on those resources and the knowledge used today.

Sowell's focus on knowledge echoed Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek, who, in his 1945 essay The Use of Knowledge in Society, exposed classical economics' flawed assumption of perfect knowledge as the dangerous bunkum that every market participant (i.e. all of us) knows it to be.

Hayek began with:

The peculiar character of the problem of a rational economic order is determined precisely by the fact that the knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess.

... The shipper who earns his living from using otherwise empty or half-filled journeys of tramp steamers, the estate agent whose whole knowledge is almost exclusively one of temporary opportunities, or the arbitrageur who gains from local differences in commodity prices are all performing eminently useful functions based on special knowledge of circumstances of the fleeting moment not known to others.

It is a curious fact that this sort of knowledge should today be generally regarded with a kind of contempt and that anyone who by such knowledge gains an advantage over somebody better equipped with theoretical or technical knowledge is thought to have acted almost disreputably.

Tragically, the Bretton Woods decision to accept interventionist Keynesian aggregate demand management as its accepted global economic policy framework condemned Hayek's market-led ideas to the sidelines for thirty years. With it, the opportunity for untold supply-side growth potential was lost.

Eighty years later, politicians and policymakers still consider the price mechanism with suspicion, disdain, and hostility despite its unrivalled means of resource allocation and wealth creation.

Sowell simply put it:

The fatal attraction of government is that it allows busybodies to impose decisions on others without paying any price themselves. That enables them to act as if there were no price, even when there are ruinous prices - paid by others. It is hard to imagine a more stupid or more dangerous way of making decisions than by putting those decisions in the hands of people who pay no price for being wrong.

Last week, a Times editorial article, Command Economics, said:

Competition informed by consumer preference is a better mechanism for generating successful products at affordable prices than anything dreamed up by bureaucrats. And until the day comes when scarcity is banished, and money and self-interest with it, that will remain the case.

Despite the insurmountable evidence of the damage done by enforcing price controls, politicians still believe that something must be done about so-called unfair prices. Recently, their attention has ranged from wages and prices of imported EVs (unfairly low) to holiday and concert tickets, property rents, and everyday groceries (all unfairly high).

However, any commodities trader will tell you the best cure for high prices is high prices. Price movements are critical to a well-functioning economy. Price rises communicate shortage to a market's participants. Supply increases, demand lessens, and customers seek substitutes. The recently weakening oil price is a case in point. As Doomberg pointed out, the biggest growth area in the trucking industry is tractor units powered by natural gas, an effectively free fuel source produced as a trapped by-product in the US shale regions.

The widespread misunderstanding of how markets' impersonal price discovery process delivers spontaneous and unintentional benefits allows politicians to bear gifts to the disadvantaged and the rent-seekers and grifters arguing their cause. And politicians cannot help themselves.

As Sowell said:

People who depict markets as cold, impersonal institutions and their own notions as humane and compassionate have it directly backwards. When people make their own economic decisions, taking into account costs that matter to themselves and are known only to themselves, this knowledge becomes part of the trade-offs they choose, whether as consumers or producers.

Howard Marks concluded his memo with his thoughts on the importance of a functional price mechanism in a well-functioning economy:

The incentives provided by free markets direct capital and other resources where they'll be most productive; they prompt producers to make the goods people want most and workers to take jobs where they'll be most productive in terms of the value of their output. They also encourage hard work and risk-taking.

In contrast, if markets are made less free – that is, if they're forced to follow government edicts rather than the laws of economics:

Capital and raw materials will be directed to places other than where they'll be most productive;

Producers will fail to make the things people want most and instead will make things the government thinks people should have;

Workers will be assigned to work where they'll produce less than they otherwise might, and

Hard work and risk-taking won't take place as much since the rewards for doing those things will be capped and, in some cases, redirected to people who didn't do the work or take the risk but whom those in control deem deserving.

Incentives and free markets are essential for a high-functioning economy, but their existence assures that some members of the economy will do better than others. You can't have one without the other.

A vital component of a well-functioning economy is its capital market. For investors, it is a critical market to understand. A few weeks ago, AQR hedge fund manager and quant theorist Cliff Asness released a paper entitled, The Less Efficient Market Hypothesis.

In the late eighties, Asness was a teaching assistant for Chicago Nobel laureate Eugene Fama and his co-author of the three-factor model Kenneth French, high priests of the efficient market hypothesis. He later completed a PhD thesis on the effectiveness of momentum trading before a career at Goldman Sachs Asset Management and his fund Applied Quantitative Research (AQR).

Rather than make a case for or against the efficient market hypothesis, Asness focuses on what he sees as the declining allocative efficiency of our financial markets over recent decades. their growing inefficiency. He concludes that markets are much less efficient using time series analysis of value spreads (the ratio of expensive stocks to cheap stocks) over the last forty years.

Asness' summary is threefold:

A relatively efficient stock market is important for society.

I believe the stock market has gotten less efficient over my (now quite long) career.

If so, this means disciplined, value-based stock picking is both riskier and likely more rewarding in the long term.

Substacker, Brainless Investing usefully summarised:

What are investors doing about it?

Indexing more

Hiding in private equity

Moving to momentum/trend following

The most interesting of these three for me was private equity. Asness points out that the low liquidity, lack of daily prices, and the fact that PE isn't marked to market fix a lot of the behavioural mistakes the public markets force investors to make. The downside is that the trade is getting crowded, and the returns will likely be lower than in the public markets.

What should investors be doing?

Cliff offers 5 pieces of advice:

Try to become as logical and rational as possible while recognising that you're human and can't be perfect.

Study history

Recognise that drawdowns and underperformance feel longer than they are.

Have as long of a time horizon as possible

"A long-term horizon is the closest thing to an investing superpower."

Look at the portfolio, not individual pieces

If you're actually diversified, something will always be underperforming. Remember why it's there.

Accept that higher rewards come with higher volatility. Size your positions appropriately

Improve your process

Here are Cliff's conclusions:

Markets are less efficient

Technology, gamification, 24/7 trading on phones, and social media are likely the biggest culprits

Ups and downs will be bigger and last longer

That will make more money for people who can stick to it long-term, but it will be harder to do so

Indexing is a very reasonable option for those who can't stick with it

Old-school, active value and quality stock-picking have had lots of people leave the strategies

It creates an opportunity for smart investors to take advantage of it.

Prices matter because they inform free agents what is happening in parts of our world that 99% of its people know nothing about. The failure to adopt this concept explains the unnecessary historic poverty and human suffering in Communist China, the Soviet Union and today’s North Korea and Cuba.

Prices also matter in stock markets, and as Cliff Asness highlights, relative value matters to protect and grow your wealth. However, as David Einhorn and others have pointed out, the process by which liquid and informed markets can assist your value trades revert to their mean is breaking down. This is how Einhorn explains it and how he is dealing with it: